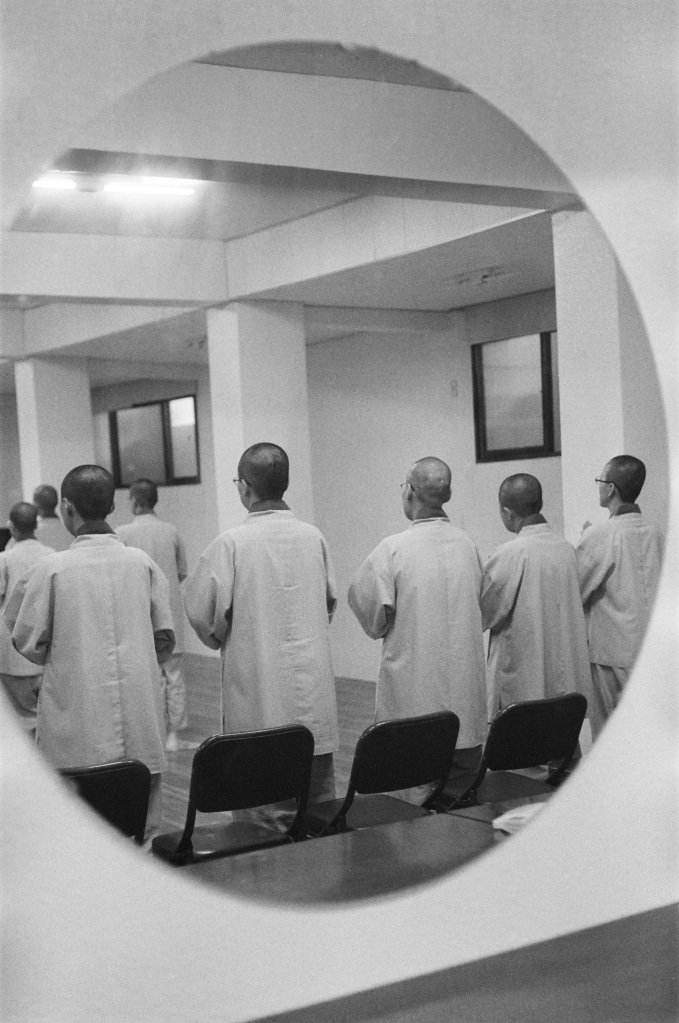

graduation: reflection

Nikkormat FE2, Kodak TMax 400

Nikkormat FE2, Kodak TMax 400

Children’s Education Department, Summer 2011 Children’s Buddhist Camp Opening Ceremony

The 48th class of Unmun Monastic College graduates today.

The pictures, as well as the stories, will continue to come out over the years.

But, for now: congratulations to all my sisters, and those at other seminaries around the country this winter.

Thank you to our original Teacher, the Blessed One, Sakyamuni Buddha, and to all those who have

carried the lamp through the ages that we too may receive the teachings and practice the path.

Thank you, deeply, to all our senior monastics, older and younger brothers and sisters in the Dharma,

our families, our donors and supporters.

May our precepts, study, and practice benefit all beings!

tongdo-sa 1.2.2012

Dok Sang (德上) Sunim, originally from Seattle, WA and currently a first-year student at Tongdo Monastic College

Dok Sang (德上) Sunim, originally from Seattle, WA and currently a first-year student at Tongdo Monastic College

Despite the first snow of the year—which closed Unmun Pass, between Cheong-do and Ulsan—I made it “over the mountain” today to visit Tongdo-sa. Tongdo-sa is not only one the Three Jewel temples in Korea, known as the “Buddha Jewel Temple” because it houses Sakyamuni Buddha’s relics, it is not merely one of the largest temple complexes in the country, it is not simply a well-known full-training temple for monks: it also has four of our novice monks from the international sangha. I met up with two of them today before having tea with the Head of Lecturers of their seminary. Unfortunately, I could only talk Dok Sang Sunim, above, into a picture. His older brother, Dok Jang Sunim, firmly refused to have his portrait taken, alas.

Tongdo-sa is what’s known as a “full training monastery,” or cheong-lim. For those who read Chinese, the characters are below as inscribed on the stone pillar marking one of the boundaries of the temple complex. Chinese readers will also notice the formal name for the temple in its function as a training monastery, Yeong Chuk Full Training Monastery (yeong-chuk cheong-lim). Yeong-chuk is both the name of the mountain on which Tongdo-sa is located as well as the Sino-Korean for Vulture Peak Mountain (Rajgir). In order to qualify as a cheong-lim, a temple complex must have a seminary; a graduate seminary; and a seon bang or Zen hall associated with it. In addition to having all of these, Tongdo-sa is also a large, bustling complex with a labyrinthine layout of side-altars arranged around the temple’s central focus: the bell-shaped stupa housing the Buddha’s relics.

Tongdo-sa is one of my favorite temples in Korea. I first visited Tongdo-sa nearly 8 years ago, when I was a lay-woman and traveling around Korea visiting temples; I spent the night at Naewon-sa, a bhikkuni seon bang, and caught a ride to Tongdo-sa the next morning with two of the Naewon-sa nuns heading there on business. It was spring. The currently naked cherry blossom trees lining the long main avenue leading up from the lower entrance gate were then in their full glory. Today, sunlight filtering through the pines and glinting on the ice clinging to the edges of the stream flowing down from the mountain caught my attention. And instead of the anticipatory trepidation of entering an unknown temple complex, wondering what it might be like, feel like, today I felt the easy anticipation of walking toward a friend’s house.

Stone pillar inscribed with the full training monastery’s name

Stone pillar inscribed with the full training monastery’s name

I met all the international monks enrolled Tongdo-sa this past summer, when we gathered for the annual foreign monastics’ forum. I was amazed by their diversity: one Czech, one Nepali, one Chinese, one American. A Japanese monk graduated several years earlier. Of course, I always appreciate meeting other Western monastics, because I get to experience the rare feeling of blending in.

The front gate of Unmun-sa at 7:20 a.m. Cold. Very cold.

The front gate of Unmun-sa at 7:20 a.m. Cold. Very cold.

Compared to the chill winter landscape I slipped and slid over to get to Unmun-sa Bus Station (and it was due to slick roads that the buses weren’t going over the pass this morning, waiting for the thin sheen of ice to melt), the early afternoon was warm. Cups and cups of tea with Tongdo-sa’s Head of Lecturers along with what was, for me, great conversation about the process of seminary life and the education system for the sangha, followed by a little time with two doban before heading over the now-thawed mountain road: a good day.

the little new year

About 6 a.m., December 20th, looking toward “The Hall of Blue Winds,” or 청풍료, and Reclining Tiger Mountain, 호거산

One of the major differences between the monks’ and nuns’ seminaries in Korea is that the monks organize their school-year, including vacations, around the schedule of the Zen Halls: when the winter or summer retreat ends—and all the Seon monks are traveling—student-monks also go on vacation. The nuns’ vacations, however, correspond to the major holidays that occur each season. Someone told me the reason for this difference in schedules is two-fold: one, by having different vacations, it’s hoped that the sami and samini sunims won’t mingle. Two, bhikkuni temples in Korea rely more on the home temple’s monastic community to host celebrations, and we’re needed at home to help out with preparations and ceremonies.

And so, two days shy of the solstice, we emptied out into the indigo-blue dawn and scattered across the country. Solstice not being as large an event as Lunar New Year’s, Buddha’s Birthday, or the end of the summer retreat (Ullambana), some nuns receive permission from their teachers to go elsewhere for the four-day break. I personally had visa paperwork to take care of, as well as some organizing to do ahead of our impending graduation, so I went to my home temple and forewent any other plans.

Ji Mun Sunim and Hye Oh Sunim at the ticket counter at the Unmun-sa Bus Station, which doubles as a small convenience store.

Although I used to travel mostly by bus between school and home, not only does that mean three different buses and take the entire day, I get carsick. It turns out that I can catch the train at Ulsan Station, which is just over Unmun Pass, and make it back to Gunsan in North Jeolla Province faster, with only one transfer in Daejeon (although I do have to switch train stations, moving from the Gyeongsan Line to the Honam Line) than if I go by bus. I like trains. Unlike buses in Korea, which seem to swerve even more than the proliferation of mountain roads requires, trains move in swooping curves or sail on straightaways, in motions vaguely epic instead of dizzyingly nervous. Something about them soothes me; I like watching the scenery; I love the little country train-stations; and I never get trainsick, a major bonus. Additionally, that day I had to get up to Seoul to take care of business before heading back down toward the provinces, and the only way to get to Seoul and onto anywhere else in a day is if you go by high-speed train.

Heading “over the hill” with me were a few of my classmates. It struck me that this was, for most of us, the last bus to Ulsan we would ever ride together as students. It wasn’t melancholy, but it was poignant. All things arise, they abide, change, and fall away. A week from today, I will no longer be a student-nun, but a graduate.

Hyeon Oh Sunim enjoys a last coffee at Ulsan Station.

Hyeon Oh Sunim and Hye Oh Sunim waited for the train going in the opposite direction, toward Busan, and we stood waving goodbye to each over the tracks.

Waiting: 9:14 am.

Our trains had the exact same departure time, 9:22 am, but my train came into the station first. I boarded and settled down. The trip to Seoul Station would take roughly two hours, and I would get off the train during the lunch hour. I had to go to Jogye Order headquarters, to pick up my visa extension paperwork and ask about the exam for full precepts that I and another foreign monk will sit in the spring. I would find out only once I’d visited Jogye Order that both reasons for my trip to Seoul would be to no purpose: I can now download my paperwork off the Jogye Order website, and no special accommodations will be made or given for foreign monastics sitting the exam.

Picture of Kim Jong-eun in the Choson Ilbo, with a family tree showing all the descendants of Kim Il-sung below. I was surprised to see that each generation has typically had two or three wives, with numerous children; many are missing, leaving, as desired, only one clear line of inheritance to Kim Jong-eun.

Before I understood my trip’s double unnecessity, though, I waited out the 30 minutes remaining to the lunch break in the Social Bureau, looking over the Choson Ilbo. Kim Jong-il’s death had been announced the day before, and the news was all about him, North Korea, and Kim Jong-eun, his son and successor. Everywhere, everywhere, Kim Jong-il stared out at us. Kim Jong-il’s blank paper eyes looked out in eerie multiplicity from the layers of newspapers lined up for sale at the subway station kiosks. The TV news stations on at the train stations reported redundantly on North Korea’s announcement, the viewing of Kim Jong-il’s body, Kim Jong-eun’s public appearances, in a way that reminded me of a less hysteric but no less obsessed CNN.

Václav Havel, the former president of both Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic, writer, poet, playwright, dissident, national hero and Nobel Peace Prize nominee,* died the same day North Korea announced Kim Jong-il’s death. I tried to talk about Havel with my classmates over coffee; they didn’t know who he was. East Europe, 1989, rung no bells, even though both nuns were in their late 40s and would, if anyone did, have reason to remember the events of 1989. But then again, the history I learned to hold close is the history of the West, the Cold War, eruptions of democracy; I learned to value history only as it related to the rhetoric and propaganda of my own country.

I waited in vain for something about Havel to appear on the TV. Even on the scrolling red news-strip at the bottom of the screen. Nothing. I saw nothing about him in the newspapers, either, and writing this now I feel vaguely Learian: Nothing, nothing, nothing.

The doors of bureaucracy; in the background is Jogye-sa.

After the nice young man in the Social Bureau printed out the extension forms for me, I went down a floor and tried to talk the Education Bureau into allowing some kind of lee-way for foreign monastics who take the bhikku/bhikkuni exam and failing to elicit anything more than a bored dismissal, I left Jogye Order. I wasn’t looking for the usual lower standards for us; I was wondering if we could do something like, possibly, take the test in English. Not this year, it’s too late; but maybe in the future? I was the only one with any enthusiasm for the idea. I walked out the doors and down the avenue, toward Gwanghwa-mun. I went to Kyobo Bookstore, hoping to find Milan Kundera’s Unbearable Lightness of Being. They didn’t have it. I picked up a new translation of selected Tranströmer and The Best European Short Stories 2011 instead, in a mild pique. No Kundera! And nothing about Havel! Only dictators and military states and recalcitrant bureaucracies!

I went out for Indian food, hoping dal tarka and roti and masala tea might be good comfort food. It was. Then I went back to Seoul Station and got on a south-bound train, to go home for the solstice.

Preparing small dumplings of glutinous rice-flour, to go into the solstice porridge.

The next day we made ong-shim-i, the small round glutinous dumplings that go into the traditional red mung-bean porridge. Red, to drive away demons and evil energies. I’ve never heard anyone talk about winter solstice as a kind of All Hallow’s Eve, but why else would we be concerned about warding away evil spirits, if not because at the winter solstice the veil between the spirit world and the human world grew more traversable? Why not, unless it was because we humans, who are in the Korean world always available to the influences of spirits, are even more vulnerable at the solstice, the fulcrum of the balance between light and dark?

The ong-shim-i are made to represent the returning sun, the Abbess of our seminary told us before we went on vacation. She didn’t then equate the dark purple-red porridge with the night, and I also resist making that symbolic equivalence even though the image works nicely. No; red is for protection and blessing in East Asia, and that’s why we make solstice porridge out of red mung-beans.

Mun Bosalnim rolling ong-shim-i.

It’s not as easy as you’d think to roll nice round dumplings. Skilled hands can place up to three pinches of dough in the palm and roll them quickly to spherical sameness, without mashing any of the little lumps together. I tried three dumplings at a time, and couldn’t manage the task, so I kept it to two dumplings.

The bosalnims, our women congregants, took over the making of the actual porridge, a laborous process taking up to several days. The mung beans must be soaked, then boiled, then strained, then re-boiled. The thick paste sinks to the bottom of the enormous cast-iron cauldron we use and tends to burn if the fire’s too hot underneath it or it’s not stirred regularly enough. The basic porridge can be neither too salty nor too bland. People add either sugar or salt to their individual bowls later, at the table.

On the actual day of the solstice, we filled two hundred square Tupperware containers with the porridge (re-heated and with the dumplings added in). These were offered at the main altar, all the side-altars, the ancestors’ altar. I couldn’t take any pictures because I was working—as per the reason for our vacation in the first place, to help out—and then helping conduct the ceremony. (I hit the moktak.) We then handed out the containers to all those who came to the midday service. The actual solstice was in the afternoon, about 2:20, and the Abbess of our temple instructed everyone to recite the Heart Sutra over the porridge before sharing it with family and friends at home. I made a quick run to my local immigration office and filled out stage-one visa extension paperwork, then made it back home in time to help with the quick afternoon solstice ceremony. (I hit the moktak again and read name-cards for the blessing.)

That evening, preparing to leave the next morning, I arranged my room, but less carefully than usual. It was December 22nd, and in another two weeks—a graduate—I would be back in this room anyway. Major organizing could wait.

I usually take the 6:05 am bus, which I can either ride all the way to Daegu or, as I planned to do this time, ride it only to Iksan and then get back on the railway. I thought I would go to Busan before heading back to school, to visit Gwangseong-sa, the Tibetan temple I attend. Maybe Geshe Sonam, the abbot, would be home; and even if not, I could do my practices and say hello to Geshe Lobsang.

Gunsan Intercity Bus Terminal, picture taken summer 2011

The older lady who runs the convenience store in the bus station was already open at 5:30 am. I bought motion-sickness medicine. Even the 40-minute ride on straight roads through the rice and barely fields of North Jeolla makes me queasy. Better safe than sorry. The store-owner has been watching me leave for school before the sun is up at the end of every vacation for four years. We exchange pleasantries. She’s Catholic, but I tell her to come to temple sometime. She smiles and laughs, yes, yes.

Iksan Station, with the Seoul-bound KTX pulling up to the platform.

I caught the train bound for Seoul, got off in Daejeon and switched back to the Gyeongsan Line and got on a train to Busan.

Gwangseong-sa, “Korea Tibet Center,” Busan.

Geshe Sonam wasn’t at Gwangseong-sa. He’s in India for the Kalachakra Initiation. Geshe Lobsang was home, though; as well as the gelong-la doing a 1000-day kido, reciting the entire Tibetan canon. “I’m reading Tsong-kha-pa now!” he told me, smiling. Originally from Ladakh, he’s read the entire canon twice before. I asked him how he learned English. “Oh, in Ladakh we have many tourists, European, Australian, some American. I learn from talking to them.” His hands are rough, chapped; he looks cold. I wouldn’t be surprised if the cold in the Dharma Hall was what caused the chapping. I remember how the monk who did the 100-day kido for Mu Sang Sa the winter I sat retreat there struggled to keep the skin on his knuckles from splitting in the sub-zero, bone-dry air of the Hall. Geshe Lobsang looked less miserable, dressed in only a single maroon sweatshirt over his lower robes. Gelong-la, on the other hand, had a hat askew on his head even during lunch and buried himself under a comforter while reciting in the Hall. I finished my prayers after lunch and then retraced my steps: street, subway, station, descent at Ulsan, taxi, bus station, bus over the pass, get off, walk up the road, enter the gates.

Afternoon, the path to Unmun-sa. Picture taken December 25th, 2011.

The period between the winter solstice and the lunar New Year’s, which is January 23, 2012, is typically referred to as “the little (new) year.” It’s one of those liminal periods, like a leap year, that emerges out of the overlap between two slightly different systems, in this case, the solar and the lunar. I like this “little year.” It lacks the pressure of a New Year or a Solstice, the once-a-year One Day that we typically take more seriously than we ought, relying too much on the concept of a significant singular moment. Resolutions, reviews, best-of’s, all congregate around this one day, New Year’s (and usually the solar new year, at that). But to spread out the significance over a month, to let it gestate, grow organically, to skip over the momentous moment and slip, slowly and smoothly, in the incrementally lessening dark, like swimming in the body of time, letting things go slow and easy, changing: it’s like entering a door. The whole body doesn’t enter, pass through, and exit a door all at once, and yet at the same time we can hardly pinpoint when, exactly, entrance became passage became exit. We just experience that we have, indeed, passed through.

(Happy solar New Year’s, which this time around is positioned nicely in the middle of the solstice-lunar new year period.)

*Correction: Havel did not receive the Nobel Prize; he was a nominee, not a recipient. Thank you to Tamarind Jordan Stowell for alerting me to the (regrettable; he ought to have received the prize) error. I’ve corrected the text.

last harvest

Three fourth-year nuns using the gaff to pluck individual persimmons from the tree, November 2011.

Three fourth-year nuns using the gaff to pluck individual persimmons from the tree, November 2011.

I saw persimmons for the first time in Korea, tasted them for the first time here. Even though we have persimmons in the States, I don’t recall seeing them in Denver as a kid and I wouldn’t have recognized them afterward in Connecticut. I knew the word, “persimmon,” and nothing more; the name reminded me of “cinammon,” and so for no better reason than association I always expect the fruit to be slightly spicy, as if it had been cold-mulling in its skin all autumn.

Harvested persimmons. The majority of these will be used to make persimmon vinegar, widely reputed to have health benefits and also an ingredient in some temple dishes.

Harvested persimmons. The majority of these will be used to make persimmon vinegar, widely reputed to have health benefits and also an ingredient in some temple dishes.

Persimmons in Korea are of two varieties, neither spiced, however. Dan-gam, the non-astringent variety, are sweet and crisp right off the branch, but hong-shi (also known as Hachiya in the West) are too astringent to eat when firm. We leave them to become a natural jelly in their skins over the course of the season and eat them then, when the tannins responsible for the astringency have broken down.

Waiting to catch falling persimmons.

Waiting to catch falling persimmons.

Harvesting the persimmon trees is the fourth-year students’ job at school. A “plush” task, in that we rarely spend more than several afternoons doing it and don’t need to break a sweat, the work requires a long gaff with a pronged end, either to twist off individual persimmons, or to grasp a main branch and shake it, causing all the persimmons dangling from the ends of the networked branches to fall. The majority of us stood below the trees with a large blanket to catch the falling fruit and keep it from bruising or breaking against the ground.

I like the etymology of the genus name, diospyros, which is glossed on a variety of sites as meaning both “fruit of the gods” and “fire of the gods.” The common name in English is derived from putchamin, pasiminan, or pessamin, all from Powhatan, an Algonquin language, and meaning simply “dried fruit.” It’s the genus name, with the suggestion of fire, that I like best. I like it best because every November, as the evenings creep further into gloom, the last fruits left on the bare black branches begin to gleam like small lanterns. They have lit many of my roads home, in North Jeolla and North Gyeongsang and to and from Seoul.

Walking into one of the small orchards.

Walking into one of the small orchards.

It’s the last fall and winter at school. Graduation is less than three weeks away. By the time we return from the short winter solstice vacation beginning tomorrow, we’ll have only two weeks until graduation. In our four years here, we’ve harvested everything from green plums (in the first year) to sweet potatoes and field greens (second year) and gingko berries (third year). That the last harvest should be both sweet and astringent is apt, I think, reflecting the nature of both community life and spiritual practice. Not sour, but tannic, that something that asks only time, until it too changes, and gives way.

in transit

Indira Gandhi International Airport, catching the flight to Lucknow. September, 2011

Dog Summer

The Wang-bok-so, or “Introduction of [to?] Coming and Going,” written by Cheng-kuan

Today, one of my classmates asked me, “Do you have a word for summer like this? I mean, this kind of really, really hot summer weather?”

I thought a moment, trying to do a quick calculation of the balance between idiomatic and literal components in translation, and answered, “Yes. We call it dog summer.”

(What I was trying to convey was “the dog days of summer,” but that in literal Korean sounds ridiculous. Although “dog summer” sounds equally funny in English, coming back the other way.)

It is dog summer here. The monsoon seems to be winding down and the next typhoon isn’t scheduled to make landfall until sometime next week, so we’re reveling in glorious sunshine and wallowing in brutal humidity. It’s the kind of weather that makes you sweat even sitting still and saps the energy right out a body: dog summer anyway you say it. The sky is a Technicolor riot every day. I’ve never shot slide film, Kodachrome, or Velvia, but those would be the only films I’ve heard of that might be adequate to the intense natural saturation of color in the sky, clouds, and trees, and I wish I had the luxury to spend some leisurely time with those colors.

Homework, however, which is not merely the bane of school-kids’ weekends but also the wrench in the otherwise fun-loving, picture-taking works of certain members of our class, has kept the majority of us inside. One of our several assignments this summer was to copy out the brief (four-page) introduction to the Avatamsaka Sutra by Cheng-kuan. Except, we had to copy it thirty times each within the four-day limit imposed by our Head Lecturer. I begged off to a mere 20 repetitions, a task which still kept me up past ten three nights running and required every spare moment during the day.

Above is one of those repetitions, a later one judging from the quality of my handwriting. Note the correction tape freely layered here and there; what malformations it hides, I don’t want to recall. I’ve posted about hand-copying sutras, or sa-gyeong, before, although this assignment differed from those acts of transcription done out of faith. Initially, we were expected to memorize the introduction, a standard expectation and accomplishment in traditional sutra halls and Korean education, monastic or otherwise; my class was a little slow with the memorization bit, so the compromise offered by our lecturer was to have us copy it out.

The horizon within our main hall has been largely filled with looming characters and layers of paper for the summer. It’s with relief, then, that we turn to the wider horizon outside, even in the heat. The sky, which is usually quite beautiful, seems particularly so this year–and I will remember this summer as the summer of intense heavens. The thumbnails I’ve included here, shot on the sly when no was looking, do not do it justice.

This afternoon.

Morning about two weeks ago, looking over the Admantine Hall to the hills beyond, during the monsoon when the sky dropped low and gray every day, if it didn’t outright pour.

Dawn, about a week ago, looking over the Vairocaina Hall, on a day that turned very rainy around midmorning.

Where everything needs everything else

Shoes and Paddy, South Chung-jeong Province, Seocheon.

In the Hua-yen universe, where everything interpenetrates in identity and interdependence, where everything needs everything else, what is there which is not valuable? To throw away even a single chopstick as worthless is to set up a hierarchy of values which in the end will kill us in a way which no bullet can. In the Hua-yen universe, everything counts.

Francis H. Cook, Hua-yen Buddhism: The Jewel Net of Indra

There are a thousand hacking at the branches of evil to one who is striking at the root, and it may be that he who bestows the largest amount of time and money on the needy is doing the most be his mode of life to produce that misery which he strives in vain to relieve.

Henry David Thoreau, Walden

To everyone who has left comments here during the past couple months, thank you: I’ve read them all but haven’t had time to reply. Housekeeping matters here, especially concerning resizing the photos in old entries to accommodate the new template (which is also begging the question, to keep or not?, at present) are in a woeful, neglected state.

In about a week or so, my class will finish Cheng-kuan’s lengthy introductory commentary to the Avatamsaka Sutra and finally enter the Sutra proper itself. Hua-yen, or in the Korean pronunciation, Hwa-eom Buddhism is a specific aspect of Chinese Buddhist thought and history that I’ve had to approach in Western literature mostly from side-paths. With the exception of three books on Hua-yen Buddhism in English–one by CC Chang, one by T. Cleary, and the last by Francis Cook–it’s easier to find extensive resources on the various components that are drawn together in the great network of Hua-yen though: Yogacara, Tathagatagarbha, Chinese influences on Buddhist thought, Ch’an. In between the main thrusts of these movements and histories, Hua-yen runs like an underground stream, surfacing here and there but rarely studied in its full. I gave up on CC Chang’s book quickly. He was an notable scholar but too in awe of the Buddhist religion to reign in his prose or some of his judgements in his scholarly work. Cleary’s book I will read as I study the sutra itself (and his translation of it), since mostly focuses on translations of various treatises on the sutra by the patriarchs of the tradition. Cook’s book, however, is both accessible and well-informed, written from a perspective that both deeply esteems the Hua-yen Sutra and has spent time considering the text’s relevance to the world of cast-off shoes and human relations, the environment and society.

I have a thing for the cast-off objects of the world. Not that I am a great conservator, an accomplished economist of the not-one-rice-grain-wasted school, not that I am immune to the lure of shiny new things. (I am particularly susceptible to new pens, new notebooks, new stationary pads, new books; less so to new shoes but not to new rosaries, somewhat skilled at deferring the hunger for new teacups but not above pestering a friend to give me one as a present or shamelessly admiring a handsome coffee mug. I am a consumer trying to undermine her own habits, and only partially successful.) But I am nonetheless concerned with what has been cast off, curious about their new existences after their initial and obvious function has been set aside. These shoes were waiting just thus on the embankment of a paddy in South Chung-jeong Province last August. Are they truly cast off? I don’t know. Perhaps they’re just resting, until the farmer returns to the paddy to work.

This curiosity, at first aesthetic, takes on a new importance in the light of the Avatamsaka Sutra. Although I didn’t chose to include Walden on my summer extracurricular reading list because I knew that Thoreau would speak so directly, from his own experience and view, to some of Hua-yen’s most central messages to us in the physical, mundane world, Thoreau is becoming an excellent companion. In a world where everything needs everything else, our modes of life are not individual choices without consequence, nor are our mistakes, made in ignorance or greed or even misguided goodheartedness, easily bartered away with an action of the opposite apparent value. The implication being, as I experience it in my own life, that we cannot pay the price of a cast-off pair of shoes by recycling several cola bottles. We cannot save the soul we lost in a moment of anger by loving the one we struck the next moment. Does this make our acts of contrition and repentance meaningless? No; but those acts don’t erase the past so much as guide the future. The first lesson of anger isn’t to love, it’s to not get angry. And the first lesson of casting off is not to recycle elsewhere, it is to understand that nothing is ever thrown away and forgotten, but remains, in a new form and function, continuing to affect us and be affected by us, in a world where everything needs everything else.

Morning walk, 5.7

Yesterday was Mother’s Day; tomorrow is Buddha’s Birthday. From the fulcrum between the two, sending wishes for everyone’s happiness!

At the (hidden) central point where the three main ridges in this picture meet is our school. You’d hardly know it’s there; most folk don’t until they get out of their car and walk along the traditional retaining wall that outlines the temple’s courtyards through our front gate. If you climb any of these ridges, the temple’s obvious, of course: large, geometric, carving out a sand-and-slate-colored mandala from the otherwise verdant landscape. But our visibility is only from above. From the side, on approach, the temple gives off an air of reticence. Other than our courtyard’s wall, the familiar swooping double-curve of our tiled roofs reveal us; but slowly and quietly without fanfare.

The paddy in the foreground used to belong to the temple, until the nuns stopped cultivating rice and barely. Now the lands are rented out to area farmers. The mountain in the center of the picture is one part of the larger set of peaks and ridges known as “Crane Mountain.” From the interior of the mountains, looking at the peak from an opposite slope, it takes on the aspect of a crane about to lift its wings in flight.

In the left of the picture, two ridges reach down; they form the two arms of the bowl-shaped mountain known as “Reclining Tiger Mountain.” (You can see another view of that ridge here, looking directly between the outstretched arms.) The ridge on the right side of the picture leads up to General’s Rock, a prominent part of the landscape around here.

Between the tigers and the generals, the temple maintains its low profile. Even the color and buzz of Buddha’s Birthday hasn’t brought the temple out from the mountains. It remains, as it was intended to be, a place to be sought, discovered, and seen, and nothing more.

Playing the Goddess

Our lecturer for a year and a half, from the first season second year to the end of the summer our third year, was a huge proponent of dramatizing the texts in order to get their point. As first years, we had listened, confused, to the second years who shared our hall reading what sounded like the scripts to hokey Buddhist cartoons during evening study hall: the characters were all figures from the second year texts, Dahui and the Sixth Patriarch and various emperors and a few Zen Masters plus witless students of said masters. Then we inherited that lecturer and began our own odyssey into creative approaches to the sutras.

The highlight, though, in terms of preparation, props, script, and execution, was a dramatization of the chapter on “Perceiver of the Cries of the World” (aka Kwan Seum Bosal) from the Surangama Sutra our third year. The cast was chosen from those students who paid insufficient attention during class. (Our lecturer figured if you were already paying attention, you probably didn’t need additional study aids; whereas if you attention was the wandering type, she’d give you something new to focus on.)

Bo Seong Sunim played the Goddess of Mercy herself, even digging up that lovely bit of silver scarf from the props box in the Children’s Outreach Program office. The rest of our classmates played various groups of earthly and celestial beings: gandharvas and kinnaras, nagas and rakshas, Wheel-Turning Monarchs, spiritual adepts, etc. Most of the crew laughed too hard during the performance to be taken seriously, but Bo Seong Sunim? …never broke character once.

다녀오겠슴니다!

In a soaking, chill April rain, the community assembled in their long traveling robes at 6:30 a.m. outside the office to formally bow to the senior nuns and then take off for spring vacation, which begins today. Along with a few other nuns, I’ll be staying at school this vacation to continue to fill my responsibilities and duties as the Head Chant Master in the main Dharma Hall.

For those who can’t read the hangul–Korean alphabet–of the title, “da-nyeo-o-gettsumnida” means, literally, “I’ll be back.” Minus Austrian accent, pop-culture reference, and irony. I can’t ever translate that literally for guests without laughing. But Koreans do not literally say “Goodbye” to elders, although we use the equivalent among friends. If you will, in fact, “be back,” then you say so to your elders. If you won’t be back, because you don’t live with said elders, you would say something like “I’ll be going now,” but it doesn’t sound as casual in Korean (가보겠습니다).

Right now, nestled in a warm, well-lit corner room, a box of books beside my desk (everything from e.e. cummings to T. Cleary), coffee having been brewed and shared among a few sisters taking a later bus, a small bun of good bread rustled up and cheese and apples procured for a snack, nothing to do but the morning offering service at ten, and tomorrow–weather permitting–some work in the Dharma Hall, it is vacation indeed.

Door to door

Each year, the fourth-year nuns go out on “tak-bal,” or alms’ rounds–but not for a daily meal, which is the original meaning of tak-bal, but to raise money for charity. The situation in modern temples is such that begging for staples, such as rice, flour, or vegetables, is hardly necessary; but the form and the custom remains and has, in the case of our seminary, been employed toward other ends. The money we raise goes to help prison Dharma networks and resources, provide educational scholarships to children in need, and into food banks, among other things.

Our team went door-to-door in the one-street residential section of the small village below the school. As per tradition, one nun hit a moktak while the rest of us chanted Sogamuni Bul, Shakyamuni Buddha.

The Great Teaching

Another season at seminary begins. Now in the fourth year, my class has officially become “the class of the Great Teaching (대교반),” a reference to the single sutra which comprises our curriculum for this last year at school: the Avatamsaka, or Flower Garland, Sutra. This engraved monolith at Seokjeong-sa bears the long title of the Sutra in the calligraphy of Hye Guk (“Wisdom-land”) Kun Sunim.

Winter 2010

The largest snowfall we’ve had in years left the temple courtyards covered in late December. In America, I’ve never seen anyone use an umbrella in snowy weather, but in Korea they’re par for the course.

Ji Mun Sunim

The day before last was Buddha’s Enlightenment Day, traditionally celebrated in Korean temples by staying up all night–here at school, we sit in meditation, although at my home temple we bow all night instead.

I skipped the all-night meditation sessions. Cluster headaches have been plaguing me for the past couple of weeks–also known as alarm headaches and suicide headaches, when they start coming I start laying low. Staying up all night seemed to be asking for another headache, and so I went to bed after the first sitting session.

This is a portrait of Ji Mun Sunim, one of the younger nuns in my class. We received novice ordination together in the spring of 2006 and met again at school, to our mutual surprise.

That Brief Interlude

Despedida de Soltera, part of a conversation between Dave Bonta and Luisa Igloria.

Deok An Sunim playing the piano in the “Jewel Hall of Great Heros,” our main Dharma Hall, autumn, 2010.

Contour, form

삭발날: on the 9th day(s) of the lunar month–9, 19, 29–we shave our heads. A special meal is served during the day, consisting of glutinous rice with various energizing additions (gingko berries, jujubes, and chestnuts, peanuts, etc.), seasoned roasted laver, and seaweed soup. The two nuns here are preparing to slice the long strands of soaked and rinsed seaweed before sauteing it and adding the broth.

As an aside, this photo reminds me that I tend to underexpose my shots. I was just beginning to wean myself off of automized settings, including my favorite “aperture priority” setting, around the time I took this picture in the summer. When I switched to all-manual on the digital cameras or played with the Nikkormat, the results surprised me with more dramatic light, typically because of slight over-exposure.

Death of the Archivist

In mid-October, a decision was made to combine the head editor and camera positions for the seminary’s magazine into one position. The head camera position I had been waiting for was, within a day, gone, and I was out of a job.

Being out of a job isn’t such a big deal at a temple: there’s always other work to be done. The preemminent reason for combining two positions into one was to allow one of those two people to enter into the pool of available labor for the rest of the temple’s numerous and arguably more pressing jobs. In my case, I stepped out of the camera position directly into the shoes of “assistant class-head (부반장).”

The last official day I was allowed to carry a camera on campus–my last official day as “the camera man”–one of my dearest sisters came to visit me. She herself graduated from a different gangwon last winter and received her bhikkuni precepts this past spring. We’ve known each other for seven years, since before we shaved our heads: that’s a long time.

The picture above was taken in our soup-making area. Ordinarily, outsiders to the seminary community, monastic or otherwise, aren’t allowed into certain areas of the temple, including the kitchen, but there are exceptions to every rule. I made coffee and some of my classmates joined us, pulling out plastic chairs to make a place in front of the hearth. Coffee, conversation, some of my closest friends in either the monastic or secular world.

I have thoughts about the downsizing of artistic work and expression in the monastic community. A visitor to the gangwon from America asked me, after hearing I shot on average about 200 frames for a working session for the seminary, why I took so many pictures and what I would do with all of them. I answered that I felt a call to witness and record our lives, “as they are,” seen from the inside and sensitive to our sometimes contradictory needs.

Losing an official position means nothing for a calling; a job is not a vocation, although I’m not trying to suggest that taking pictures is a vocation for me. I don’t think I have the skill to merit that term. Still, the arts–music, poetry, literature, visual arts, and more–used to be religion and spirituality’s province. Now they are called frills, additions, “interests.” What if they are central, incorporated, and necessary modes of spiritual communication? At the very least, what if they provide the wordless, evocative footprints by which the future will follow the past we are already becoming? The death of a community’s archivist, I suggest, is not simply an end of photo albums and “souvenir shots.”

The picture above is more than a souvenir shot for me or anyone who looks at it. Although I’m not in the picture–I never am, because I’m the photographer, an essential but invisible part of the process–these people are all lynchpins in my monastic life. That’s the personal archive, where each individual in a particular location opens an endless web of stories, associations, memories and spiritual lessons. The greater archive is the story of worlds meeting, two American sisters among their Korean community, and the mutual windows and doors into each others’ lives we have become.

Bean-sprout rice

On the right, the two nuns standing are, from top to bottom, a first-year nun serving a work-rotation as the Third Helper (하채공) and the summer season’s third-year student Housemaster (원주). Scooping rice out of the cauldron are two third-year nuns, the Head Rice Cook at top left and her helper for the day at bottom left.

The bean sprouts used to make this special meal were grown by the Housemaster; to turn fresh bean sprouts into bean-sprout rice requires careful control of water and fire, and more batches of this meal end up bad than good. This one, however, was a success.

First-year student boiling dishes

At the end of each season, the first-year students boil the stainless steel dishes used by the community for informal meals in one of the kitchen’s old-school cast-iron cauldrons. Set into wood-burning concrete hearths, we have three such cauldrons: one is used every day, three meals a day for soup, and two are reserved for “special work” like boiling mass amounts of corn-on-the-cob, and boiling the dishes.

At the end of each season, the first-year students boil the stainless steel dishes used by the community for informal meals in one of the kitchen’s old-school cast-iron cauldrons. Set into wood-burning concrete hearths, we have three such cauldrons: one is used every day, three meals a day for soup, and two are reserved for “special work” like boiling mass amounts of corn-on-the-cob, and boiling the dishes.

Hot. Intense: all two hundred+ dishes must be boiled, polished, rinsed, and dried in an hour. Back-breaking, from the hours-long process of building the fire and bringing over 20 liters of water to a boil to carting the dishes back and forth from the cauldron to the dish-washing area, and from and back to the main hall.

This first-year student crouches over the cauldron on the hearth itself, pulling dishes out of the water one by one and handing them off to another nun.