Second-year students teach first-year students how to prepare summer cabbages.

Latest

daily

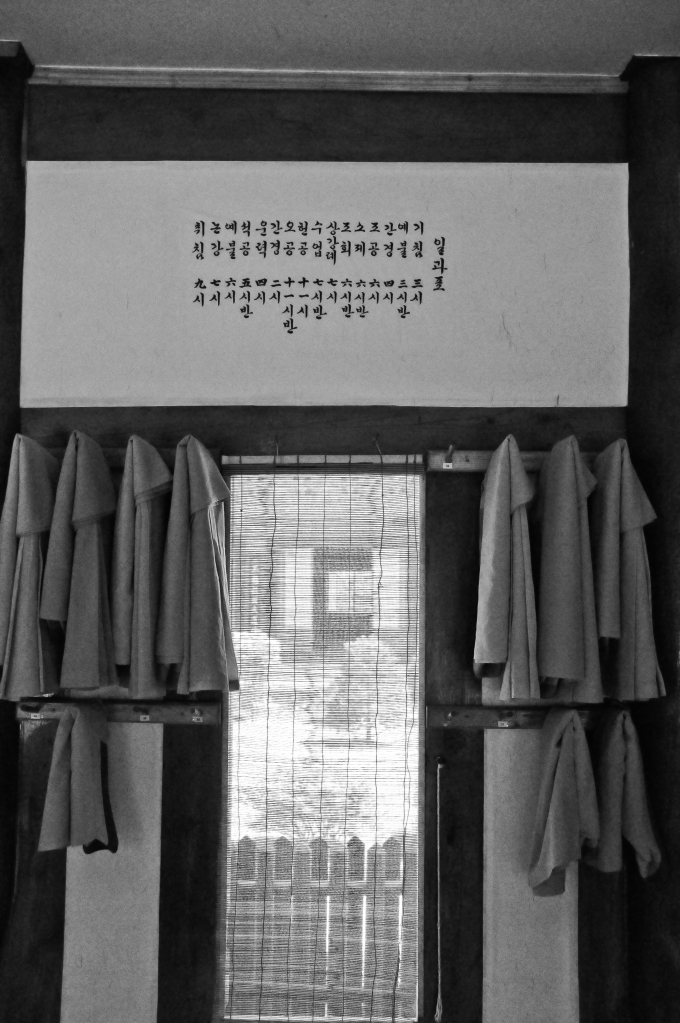

Changsam and the daily schedule, Vajra Hall, Un Mun Sa

It’s been a long time since I posted here.

I’ve done a mediocre job of keeping up with posts at (thus) but have basically ignored fts for a long while. Writing is something I can do while confined within a room or compound; photographs happen less when I’m physically constrained. Now I’m in the U.S. for the summer, at UVA in Virginia for the summer Tibetan intensive course. And it is intense, leaving as little time for photographs and writing as my busy spring season at my home temple. Daily practices of all kinds are being juggled. While I’ve been able to keep up with things in a general sense, on any given day only a few balls are actually in my hands. Sometimes one’s a camera, sometimes a computer, sometimes a blog; but always (these days) a textbook and a vocab list.

I have a backlog of edited photos, thanks to the prep work I did for a talk at the Korea Society in New York City. I’ll focus on getting some of those up, a few at a time, throughout the summer. For pictures (and really good ones!) of the summer of Tibetan, see classmate and Actual Photographer Matt Richter’s tumblr site.

Bhikkuni Ordination, April 3, 2012

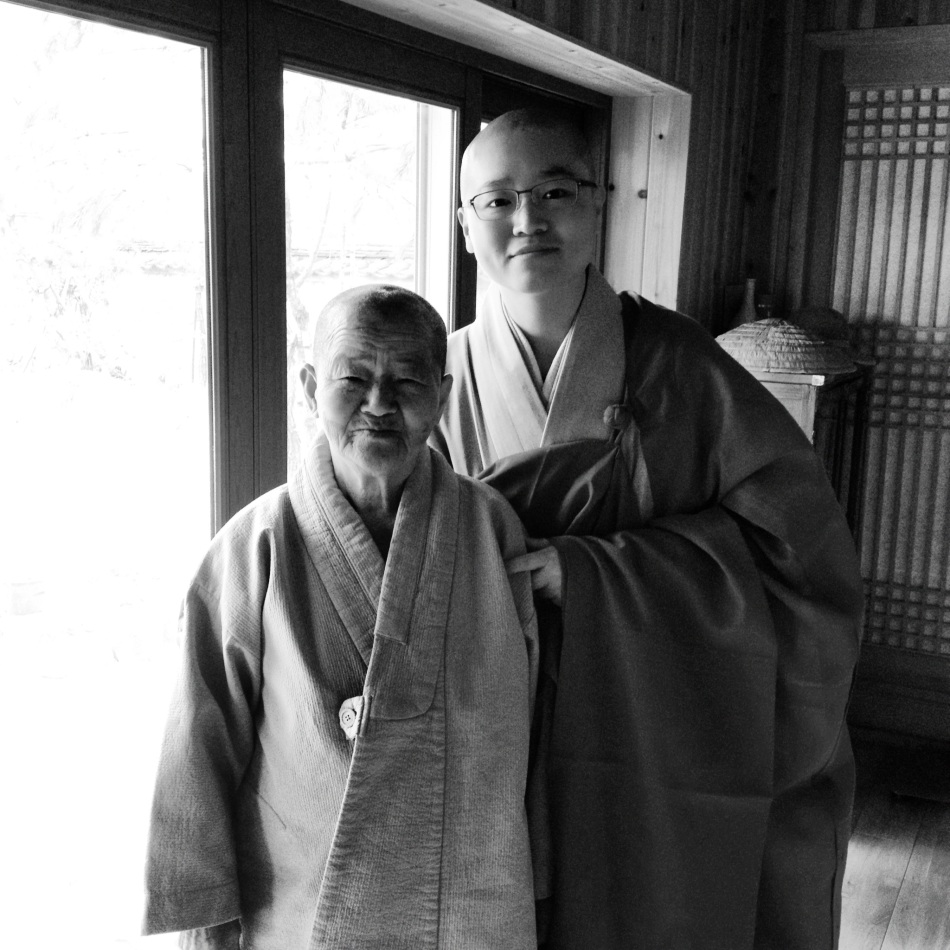

After bhikkuni ordination, with Hye Hae Noh Sunim.

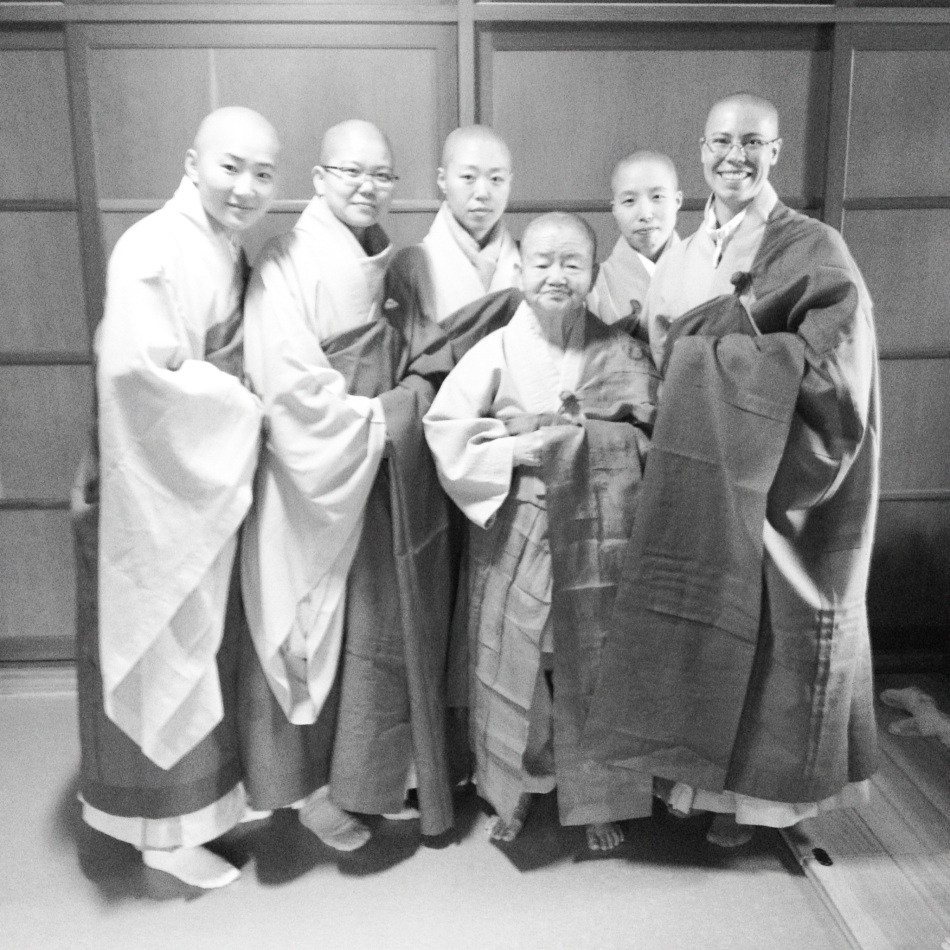

Left to right, Ji Mun Sunim, Hyeon Woo Sunim, Il Seok Sunim, Seon Myeong Sunim, Seon Joon Sunim

April 3, 2012, 3:40 a.m.

After a week-long training in the precepts, including lectures covering each section of the Pratimoksha precepts for bhikkuni, or fully-ordained female monastics, one hundred and eight women entered the Hall of Ten Thousand Virtues at Jikji Temple in South Korea and received the 348 precepts of a bhikkuni and re-affirmed her commitment to the eight “heavy precepts,” in accordance with the Dharmagupta (四分律) Vinaya lineage, from the community of elder nuns. Three acharya and seven “pure witnesses” formed the bhikkuni platform for transmission of the precepts.

When we were finished, we left the hall, ate breakfast in the formal style (a four-bowl meal, or “bal-ru gong-yang”), and then waited while the sami monks received their bhikku precepts. We then re-entered the Hall around 9 a.m. for our second ordination in front of the assembly of bhikkus. Our platform of ten senior nuns spoke on our behalf to the assembly of ten senior bhikkus, and the ordination ceremony was repeated in front of the monks. In this way, we received our ordination according to the “double platform” stipulated in the monastic regulations.

Ji Mun Sunim, Hyeon Woo Sunim, Il Seok Sunim, Seon Myeong Sunim, and Seo Ju Sunim with Hye Hae Noh Sunim

I almost don’t know what to say about our ordination. Almost; but I’m rarely someone at a loss for words for very long. I scoff at my own religiosity sometimes, mocking my love of pomp and ceremony while at the same time yearning for the glimpse of the sublime that I get from it, peeking out from under the skirts of priests and reflected, wavering, in the brass of candlesticks and offering bowls. I sniff at my own inclinations because they insinuate several things, one of which being that I am a sentimentalist, somehow cliche, and another of which being that I am unable to get past form and attain substance. It’s not that I am necessarily either of these, but the fear that I might be lurks around my love of midnight Christmas masses and my satisfaction in a well-timed rice-offering like a whisper overheard in a crowded room.

Ordination is a terribly religious business. If there is pomp, it will be on parade at an ordination. If there is form and attachment to form, it will be out menacing the community in full regalia. There are precepts and procedures and formulas and scripts. There are expectations to be met and traditions to be preserved. There is much at stake at an ordination ceremony, most of which can and will be committed to memory and later immortalized in the commentary of senior officials. If anything goes wrong, if anything goes extraordinarily well: either way, ceremonies are part of a religion’s public record and in this regard can raise the ire of those who think that function should take precedence over form. Does it really matter if the lines of the cushions are perfectly straight? Or the colors of the flower arrangements harmonious? Or whether we bowed in perfect unison or not?

I loved the training. The lectures, the group chanting of the Pratimoksha, the bowing, the repentance, the easy way a group of 108 women who received similar training at institutions across the country fell into the familiar rhythm of work and community life together. Camaraderie, and something more. A mutual respect for the difficulties we each overcame to arrive at this place, at this time, together. Shared karma and individual karma braided together like the rope of a ladder, leading us further on.

Jikji Temple, where I also received novice precepts six years ago, is beautiful. At that time, as a postulant I only looked at the ground (as befits a good postulant). I wore a track between the hall the female novices lived in for the three-week training and the bathroom and memorized the cracks in the concrete and the slope of the stairs, never once looking up to see the mountains or the the sky or the trees that grace the temple’s mandala. I was full of unresolved questions but an equally stubborn will to ordain, and the two shared space in my heart like a pair of bristling animals, granting each her territory but not allowing any trespass. I was in turmoil the entire postulant training, and I cried, overwhelmed, after our morning precepts ceremony on the last day. It would take me years to begin to shape a peace between my challenges to the system and institution I had entered into, and the practice—but not always the religion—to which I wanted to commit my life. Form and function, vessel and substance: endlessly, endlessly, I have struggled with the relationship between the two.

People ask me why I came to Korea, why I chose to ordain, why I chose to ordain in Korea. I am not singularly a Zen practitioner. I freely describe my practice as a hybrid between Korean and Tibetan practices. I also feel the Tibetan canon has much to offer that the Chinese canon (the one which is authoritative in Korea) cannot. I am more of a Madhyamakan than a Tathagatagharban; big trouble in East Asia. Given all that, Korea is not the logical choice for me. It was a choice among others, and I made it partly because I was told I could study the sutras and sit Zen if I wanted, but even more so, because I could receive precepts from the double platform. As a woman and an American, I cannot tell you all how important this was to me. From the day I met the Buddha-Dharma, I also met the sangha; and from the moment I met nuns (Tibetan-tradtion nuns, in Nepal), I wanted to be a part of their community, in the widest sense of “female monastics.” I also felt that ordination in America would be very difficult. I did not have a strong relationship with any one Tibetan teacher, and didn’t know how to forge one to seek ordination. I didn’t find any large communities of bhikkunis in the West at that time. I did not have a connection with Thich Nhat Hanh’s community, even though the Plum Village and Deer Park Monastery communities are among the most stable and structured large-scale monastic communities in the West. Other than going East, I just did not know what to do. Something just didn’t feel right for me in the States.

Being the nerd that I am, I researched monastic precepts after I left Nepal eleven years ago. I knew more about bhikkuni precepts, platforms, Vinaya lineages, and controversies than I did about basic Buddhist teachings for a couple of years. What I learned left me convinced that not only would I be satisfied with nothing less than full ordination, meaning the full precepts of a bhikkuni in addition to the ten “novice” or sramenerika precepts that constitutes the first-stage of ordination, but that it had to be done “legally.” That meant a community of nuns to transmit the training and the precepts, and another assembly of monks to affirm the ordination. This is the “double platform.” In practice, there are many nuns, including a large number in the Tibetan tradition, who don’t receive bhikkuni ordination. (In the case of Tibetan nuns, this is partly because the bhikkuni lineage died out. The ten precepts can be given to a woman by a bhikku, or male monastic, but strictly speaking, bhikkuni are required to ordain other bhikkuni; bhikku alone cannot transmit the bhikkuni precepts, nor can bhikkuni ordination by the nuns community alone without a second ordination by the bhikku community be considered a “legal” bhikkuni ordination.) Even in Korea, the double-platform wasn’t revived until the early 1980s, after a lapse of how many years I don’t know. Prior to that, bhikku only gave the bhikkuni precepts if a nun received them at all. Many monks and nuns held the ten novice precepts their whole lives, satisfied with that training and receiving all the respect and honor due to a monastic, with no one much bothering with the distinction between novice and fully-ordained. There is a lot more that could be said about monastic traditions and full ordination, but I’ll leave it at this.

When the Abbot of my Zen center in Connecticut told me Korea had a double-ordination platform for women and that I could receive not only monastic training, but scriptural training in Korea, I decided to come here and test my karma with this country. I had enough good karma to find a community and a teacher (Unsa Sunim) to take me. That was seven years ago. Although there were many, many other factors contributing to my decision to seek ordination in Korea, being able to receive bhikkuni precepts from the double-platform has always been the kernel and the core of that decision.

Whether I had “correct” or “clear” motives is not so important anymore; I am convinced that no one knows what they really want or feel until they’re in the thick of community and ordained life. Only when the pressure is on and the questions are sharp, sharper than they ever were before and sharper than you dreamed they could be, only then do you begin to understand why you’re willing to stick with the commitment you made. At least, that’s how ordained life as been for me. Not one decision, not one commitment, but a ceaseless recommitment and ever-deepening understanding of how and why I came here, and how and why I will continue to practice as a monastic.

I’m not sure how much I can talk about the details of the ordination ceremony. Sometimes ordination ceremonies are public, sometimes they aren’t; in Korea, outsiders are not permitted in, and certainly no non-monastics or monastics who are not of the correct monastic age (a novice nun who hadn’t received her intermediate precepts would not be allowed to even observe the ceremony, for example). But it was beautiful to me. The liturgy, a mixture of classical Chinese and formal high Korean, was intelligible to me for the first time ever; I understood only the Korean of my novice ordination and only bits of my intermediate/probationary ordination two years ago. The call-and-response, the swell of voices, the ritual of requesting everything three times; calling all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to witness us and be our teachers and guides; the array of senior nuns on the platform, their severity, their grace; the sear of the precepts’ burn, the piney smell of the mugwort and incense as they smoldered; the hummingbird-beat of the moktak while we chanted the great dharani; the weight of the seven-patch robe of a dae kasa, the kasa of a fully ordained bhikkuni, the stiffness of the new material, the way I couldn’t untangle mine enough to give me space to properly fold my feet under it while we knelt, and so I kept tugging and tugging at while tucking my feet into a small ball so they wouldn’t peep out from under my robes; the nuns intoning in the dark and then the monks several hours later, “You will now receive your precepts-body;” the injunction to only use our Dharma names. Hearing that the Buddhas of the ten directions, the protectors, and all beings rejoice when someone receives precepts. Being told that our practice, as bhikkuni, is to “cease all wrong-doing, cultivate all good actions, and benefit all beings.” Hearing and feeling, truly and deeply and with incredible gratitude and joy, that as of this moment, I have a new life.

I guess that makes me a born-again monastic. There are worse things to be.

After the ceremony, a small group of us went to bow to the grand-teacher of one of our classmates. Seo Ju Sunim and I met seven and a half years ago as lay-women during the three-month winter retreat at Mu Sang Sa. We met again as a monastics at Unmun-sa, where were in the same class. Her grand-teacher, Hye Hae Sunim (honorifically called “elder,” or “Noh Sunim”), is one of the most respected nuns in the Zen community in Korea. Seo Ju Sunim suggested we go bow to her; I only had my phone to take pictures with, so the quality (I’m afraid) is less than what I would have hoped for as a photographer. Unless I told you, I’m not sure you’d know what to look for in the picture that indicates we’re full bhikkuni, other than (in my case) the way I can’t stop smiling. Our changsam, the gray butterfly robe we wear under our kasa, has no brown stripe at the collar; we also wear plain gray regular robes (jackets, etc.), without the brown stripe at the collar and on the sleeves. Our kasa is also paneled, or patched; the man-ui kasa we wore as novices and probationary nuns had no patches, but was a single contiguous piece of cloth. I regret somewhat to see, looking at the first picture in this post, that receiving new life as a bhikkuni has not helped me arrange my kasa any better. I am perpetually unable to get my folds to fall properly.

Hye Hae Noh Sunim, whose name means “Ocean of Wisdom,” gave us a few words on hwadu practice. Then she exclaimed over the cake we’d brought her, laughed, congratulated us, and urged us to eat slices of orange. She was barefoot on a blustery spring day. She has few teeth left but very sharp hearing. She is one of the strengths of the bhikkuni community here in Korea. It is because of practitioners like her, elders who found their way to the marrow of the bone of their vocation and their practice and then built communities to help other women practice, that we were able to receive precepts at all yesterday morning. In the past lies the future, like the braids of a rope ladder, anchoring us in the moment while taking us onward at the same time.

I’ve always been aware that even though we say, “I took precepts,” this is not precise or accurate language. We don’t take precepts, they cannot be lifted like a stereo or claimed like a prize. We receive them; they are given. We don’t keep precepts, either, like a casserole in the freezer or cash in an account. We hold them, like a living thing, and we care for them, and they care for us. We may break precepts, like a heart, or a bone; but they don’t break like something inanimate. They break like we break, because they live as we live, and they die as we fail to respect and love them, to see them as that which will shape us into beings capable of helping other beings and guide us toward wisdom and skillfulness, for the greatest benefit and joy of all.

I am so grateful to everyone who has supported my sisters and me on the path. Near and far, across continents and oceans, many different lives have interwoven with mine to make this vocation possible. May I repay this debt in full, and fulfill my vows, world after world, life after life, until every being is free.

each day (new years, ancestors, and confusing chronos)

Fruit and flower offerings on the main altar

The little new year is ending. When it began, I was a seminary student on her last winter solstice vacation, heading from school outside of Daegu to my home temple in North Jeolla Province. Now I am a graduate, at home in North Jeolla, settling with difficulty into the rhythm of a temple that has, in the four years I was away at school, become unfamiliar.

Sunday, we spent the day preparing for the lunar new year’s ceremonies: first, on Sunday afternoon (the 29th day of the 12 lunar month), we made offerings to the Jo Wang Shin, more commonly known as “the Kitchen god,” in our kitchen. On Monday, the first of the new lunar year, immediately following the dawn service, we performed the rice-offering we usually perform at mid-morning, and then made offerings to the ancestors at our memorial altar.

The Jo-wang, or Kitchen God, altar

The memorial altar, with offerings for the ancestors. On the wall are memorial plaques with the names of specific individuals.

One of the first things I had to come to terms with in Korean temples was the presence of the ancestors. Not only the regular performance of memorials for both the recently deceased and ancient forebears, but also the standard inclusion of rituals and ceremonies for the ancestors in every Buddhist ceremony. The Confucian culture and values intertwined with Buddhism in Korea are the reason for this hybrid ceremony and dual metaphysics: A common question non-Koreans often ask is, “If the consciousness leaves the body, enters the bardo, and receives a new body in a new realm of existence after 49 days, what or who on earth is left to be an ancestor in this sense?” It’s not an unfair question, since what happens ritualistically in many of these ceremonies is the appeasement of the family spirits through offerings of both food and Dharma. But who or what needs appeasement and comes to partake, if orthodox Buddhist teaching would suggest this is radically impossible?

Biscuits stacked in the traditional way for offering to the ancestors

No one has offered a suitable answer to this question, at least in the context of those Koreans who are both dedicated Confucianists and devout Buddhists. The silence regarding this question seems akin to Pascal’s wager, except that it wants to have its cake and eat too (just to confuse matters) by wagering on two different metaphysical systems.

Thich Nhat Hanh is one of the few Buddhist teachers to make practices from one culture available to not only a new generation in the same culture, but even accessible for those outside the original culture. This is what he said about ancestors in a public Dharma talk at Pagoda Phat Hue:

In Plum Village, every year, we celebrate one Ancestors’ Day. And during that day we practice looking deeply in order to recognize the presence of our ancestors in us, in every cell of us. We know that our ancestors are our roots. It’s like the plant of corn has a seed of corn as a root, and when you are well rooted, then you are strong. But if you are uprooted, then you are not strong enough to confront life.

That is why in countries like Vietnam, every family has an ancestral alter in the house. Ancestral worship is what we practice. In China, also, we practice ancestor worship.

Even if you are not rich, but in your home there is in a central place, a table or a hallway, create an ancestral altar. You may have an incense bin. You may have a flower pot on the ancestral altar.

When we cry, our ancestors also cry with us. And when we listen to a Dhamma talk, our ancestors also listen to a Dhamma talk. This is really wonderful.

So, the practice is, every day, you go to the ancestral altar, and you remove the dust. You wipe the dust from the altar, you change the water in the flower pot, and you light a stick of incense and put it on the incense burner. That is the way we practice.

And why do we do that? We are getting in touch with our ancestors. It takes only one or two minutes to take care of the ancestral altar, but during the time that we clean the altar, during the time we light a stick of incense, we are really in touch with our ancestors. And we get rooted more deeply in our ancestors. We have the feeling that wherever we go, our ancestors are with us. We don’t feel alone. We don’t feel alienated. That is the goodness with the practice of ancestral worship.

Honoring the ongoing presence of family members in our lives, sidestepping the metaphysics and rituals, grounding the presence of our ancestors in our own flesh and feeling (rather than focusing on an external projection onto offerings, say), is something I can relate to. I’ve held 49-day ceremonies for my grandparents and memorials for our ancestors. I also imagine the day that I’ll finally be able to celebrate a memorial ceremony in an American way: coffee and bread, soup and salsa, cheese and crackers, casseroles and cookies, fruit and vegetables. The things my family likes to eat. If part of the purpose of ceremony is to bridge the unspeakable spaces between realms, we need to have a ceremony that reflects the realm we stand in, including the offerings. Even if you follow orthodox Buddhist teachings on the consciousness and reject the notion that the family spirits come to dine, I find little to argue with a kind of Buddhist wake, a celebration of the connection between generations which Thich Nhat Hanh so beautifully emphasizes.

Orchids offered on the main Buddha altar

Despite my different perspective on remembering ancestors, and my yearning to modify the memorial ceremonies to reflect the culture I come from, I value the way that such constant interaction with the ancestors breaks the finality of death. If the ancestors can be invited to come and dine with us, then they haven’t finally departed. They abide, and, in the Korean world, interact with us. The metaphysics of such continuance and interaction may not hold for the nitpicky Buddhist, but the emotional impact of having ancestors always responsive to us and our lives is certain.

I’ve grown away from seeking definitive ends and beginnings to things over the years since I first entered the temple. About seven and a half years ago, I was convinced that simply by shaving my head, changing my daily schedule, and receiving precepts, a corresponding inner metamorphosis would happen with the same immediately visible or tangible shift as a haircut or a ceremony. My experience has been that those internal metamorphoses are, at best, slow and circular. They seem to proceed forward only to return to a point near where they began. They do not track with chronos, and seem to function at times in direct defiance of the forward-march of a timeline. There are times of deep disjoint, when the exterior symbols don’t match the interior state, and I feel like I’ve failed to be what I present as. The gap between sign and content encourages flexibility when approaching the world; after all, who knows what’s gestating in the unseen spaces of the heart? Who knows what might emerge to break with what we expected at first glance, and shock us into letting go of our ideas?

I’m drawn to “the little new year” between winter solstice and lunar new year because it diffuses the impact of a single day over a month, confusing the meaning of renewal we usually assign to “the new year.” If there’s no one “new year,” then maybe there is no one “new beginning.” These ceremonies for the ancestors diffuse death in a similar way. We are instructed to say goodbye, even given forty-nine days to do it, and allowed our grief; then told to let the departed leave. But then, with regularity, we are told to approach the departed, that they are returned to us and with us (however we chose to understand or experience that return), and we are encouraged to sit with them, remember them, honor them, and that most basic material expression of love, to feed them.

Whichever new year you celebrate (the Tibetan New Year, Losar, is coming up on the 22nd), may each day be filled with all the potential that new beginnings have, and may you and yours throughout the generations enjoy the blessings of health, contentment, peace, and joy this and every year.

graduation: reflection

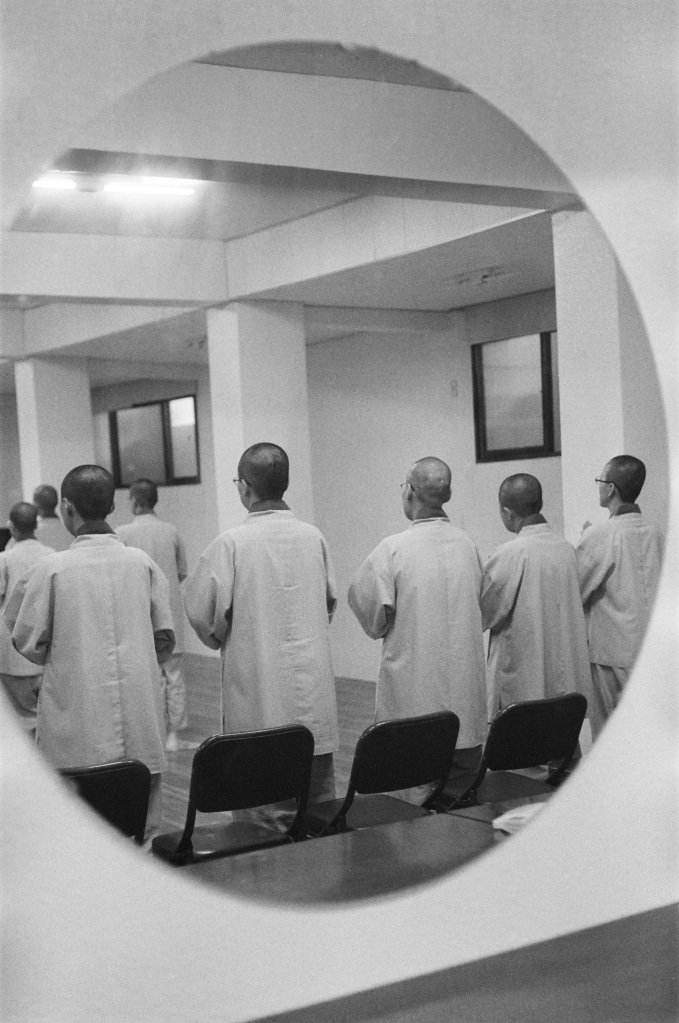

Nikkormat FE2, Kodak TMax 400

Nikkormat FE2, Kodak TMax 400

Children’s Education Department, Summer 2011 Children’s Buddhist Camp Opening Ceremony

The 48th class of Unmun Monastic College graduates today.

The pictures, as well as the stories, will continue to come out over the years.

But, for now: congratulations to all my sisters, and those at other seminaries around the country this winter.

Thank you to our original Teacher, the Blessed One, Sakyamuni Buddha, and to all those who have

carried the lamp through the ages that we too may receive the teachings and practice the path.

Thank you, deeply, to all our senior monastics, older and younger brothers and sisters in the Dharma,

our families, our donors and supporters.

May our precepts, study, and practice benefit all beings!

tongdo-sa 1.2.2012

Dok Sang (德上) Sunim, originally from Seattle, WA and currently a first-year student at Tongdo Monastic College

Dok Sang (德上) Sunim, originally from Seattle, WA and currently a first-year student at Tongdo Monastic College

Despite the first snow of the year—which closed Unmun Pass, between Cheong-do and Ulsan—I made it “over the mountain” today to visit Tongdo-sa. Tongdo-sa is not only one the Three Jewel temples in Korea, known as the “Buddha Jewel Temple” because it houses Sakyamuni Buddha’s relics, it is not merely one of the largest temple complexes in the country, it is not simply a well-known full-training temple for monks: it also has four of our novice monks from the international sangha. I met up with two of them today before having tea with the Head of Lecturers of their seminary. Unfortunately, I could only talk Dok Sang Sunim, above, into a picture. His older brother, Dok Jang Sunim, firmly refused to have his portrait taken, alas.

Tongdo-sa is what’s known as a “full training monastery,” or cheong-lim. For those who read Chinese, the characters are below as inscribed on the stone pillar marking one of the boundaries of the temple complex. Chinese readers will also notice the formal name for the temple in its function as a training monastery, Yeong Chuk Full Training Monastery (yeong-chuk cheong-lim). Yeong-chuk is both the name of the mountain on which Tongdo-sa is located as well as the Sino-Korean for Vulture Peak Mountain (Rajgir). In order to qualify as a cheong-lim, a temple complex must have a seminary; a graduate seminary; and a seon bang or Zen hall associated with it. In addition to having all of these, Tongdo-sa is also a large, bustling complex with a labyrinthine layout of side-altars arranged around the temple’s central focus: the bell-shaped stupa housing the Buddha’s relics.

Tongdo-sa is one of my favorite temples in Korea. I first visited Tongdo-sa nearly 8 years ago, when I was a lay-woman and traveling around Korea visiting temples; I spent the night at Naewon-sa, a bhikkuni seon bang, and caught a ride to Tongdo-sa the next morning with two of the Naewon-sa nuns heading there on business. It was spring. The currently naked cherry blossom trees lining the long main avenue leading up from the lower entrance gate were then in their full glory. Today, sunlight filtering through the pines and glinting on the ice clinging to the edges of the stream flowing down from the mountain caught my attention. And instead of the anticipatory trepidation of entering an unknown temple complex, wondering what it might be like, feel like, today I felt the easy anticipation of walking toward a friend’s house.

Stone pillar inscribed with the full training monastery’s name

Stone pillar inscribed with the full training monastery’s name

I met all the international monks enrolled Tongdo-sa this past summer, when we gathered for the annual foreign monastics’ forum. I was amazed by their diversity: one Czech, one Nepali, one Chinese, one American. A Japanese monk graduated several years earlier. Of course, I always appreciate meeting other Western monastics, because I get to experience the rare feeling of blending in.

The front gate of Unmun-sa at 7:20 a.m. Cold. Very cold.

The front gate of Unmun-sa at 7:20 a.m. Cold. Very cold.

Compared to the chill winter landscape I slipped and slid over to get to Unmun-sa Bus Station (and it was due to slick roads that the buses weren’t going over the pass this morning, waiting for the thin sheen of ice to melt), the early afternoon was warm. Cups and cups of tea with Tongdo-sa’s Head of Lecturers along with what was, for me, great conversation about the process of seminary life and the education system for the sangha, followed by a little time with two doban before heading over the now-thawed mountain road: a good day.

the little new year

About 6 a.m., December 20th, looking toward “The Hall of Blue Winds,” or 청풍료, and Reclining Tiger Mountain, 호거산

One of the major differences between the monks’ and nuns’ seminaries in Korea is that the monks organize their school-year, including vacations, around the schedule of the Zen Halls: when the winter or summer retreat ends—and all the Seon monks are traveling—student-monks also go on vacation. The nuns’ vacations, however, correspond to the major holidays that occur each season. Someone told me the reason for this difference in schedules is two-fold: one, by having different vacations, it’s hoped that the sami and samini sunims won’t mingle. Two, bhikkuni temples in Korea rely more on the home temple’s monastic community to host celebrations, and we’re needed at home to help out with preparations and ceremonies.

And so, two days shy of the solstice, we emptied out into the indigo-blue dawn and scattered across the country. Solstice not being as large an event as Lunar New Year’s, Buddha’s Birthday, or the end of the summer retreat (Ullambana), some nuns receive permission from their teachers to go elsewhere for the four-day break. I personally had visa paperwork to take care of, as well as some organizing to do ahead of our impending graduation, so I went to my home temple and forewent any other plans.

Ji Mun Sunim and Hye Oh Sunim at the ticket counter at the Unmun-sa Bus Station, which doubles as a small convenience store.

Although I used to travel mostly by bus between school and home, not only does that mean three different buses and take the entire day, I get carsick. It turns out that I can catch the train at Ulsan Station, which is just over Unmun Pass, and make it back to Gunsan in North Jeolla Province faster, with only one transfer in Daejeon (although I do have to switch train stations, moving from the Gyeongsan Line to the Honam Line) than if I go by bus. I like trains. Unlike buses in Korea, which seem to swerve even more than the proliferation of mountain roads requires, trains move in swooping curves or sail on straightaways, in motions vaguely epic instead of dizzyingly nervous. Something about them soothes me; I like watching the scenery; I love the little country train-stations; and I never get trainsick, a major bonus. Additionally, that day I had to get up to Seoul to take care of business before heading back down toward the provinces, and the only way to get to Seoul and onto anywhere else in a day is if you go by high-speed train.

Heading “over the hill” with me were a few of my classmates. It struck me that this was, for most of us, the last bus to Ulsan we would ever ride together as students. It wasn’t melancholy, but it was poignant. All things arise, they abide, change, and fall away. A week from today, I will no longer be a student-nun, but a graduate.

Hyeon Oh Sunim enjoys a last coffee at Ulsan Station.

Hyeon Oh Sunim and Hye Oh Sunim waited for the train going in the opposite direction, toward Busan, and we stood waving goodbye to each over the tracks.

Waiting: 9:14 am.

Our trains had the exact same departure time, 9:22 am, but my train came into the station first. I boarded and settled down. The trip to Seoul Station would take roughly two hours, and I would get off the train during the lunch hour. I had to go to Jogye Order headquarters, to pick up my visa extension paperwork and ask about the exam for full precepts that I and another foreign monk will sit in the spring. I would find out only once I’d visited Jogye Order that both reasons for my trip to Seoul would be to no purpose: I can now download my paperwork off the Jogye Order website, and no special accommodations will be made or given for foreign monastics sitting the exam.

Picture of Kim Jong-eun in the Choson Ilbo, with a family tree showing all the descendants of Kim Il-sung below. I was surprised to see that each generation has typically had two or three wives, with numerous children; many are missing, leaving, as desired, only one clear line of inheritance to Kim Jong-eun.

Before I understood my trip’s double unnecessity, though, I waited out the 30 minutes remaining to the lunch break in the Social Bureau, looking over the Choson Ilbo. Kim Jong-il’s death had been announced the day before, and the news was all about him, North Korea, and Kim Jong-eun, his son and successor. Everywhere, everywhere, Kim Jong-il stared out at us. Kim Jong-il’s blank paper eyes looked out in eerie multiplicity from the layers of newspapers lined up for sale at the subway station kiosks. The TV news stations on at the train stations reported redundantly on North Korea’s announcement, the viewing of Kim Jong-il’s body, Kim Jong-eun’s public appearances, in a way that reminded me of a less hysteric but no less obsessed CNN.

Václav Havel, the former president of both Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic, writer, poet, playwright, dissident, national hero and Nobel Peace Prize nominee,* died the same day North Korea announced Kim Jong-il’s death. I tried to talk about Havel with my classmates over coffee; they didn’t know who he was. East Europe, 1989, rung no bells, even though both nuns were in their late 40s and would, if anyone did, have reason to remember the events of 1989. But then again, the history I learned to hold close is the history of the West, the Cold War, eruptions of democracy; I learned to value history only as it related to the rhetoric and propaganda of my own country.

I waited in vain for something about Havel to appear on the TV. Even on the scrolling red news-strip at the bottom of the screen. Nothing. I saw nothing about him in the newspapers, either, and writing this now I feel vaguely Learian: Nothing, nothing, nothing.

The doors of bureaucracy; in the background is Jogye-sa.

After the nice young man in the Social Bureau printed out the extension forms for me, I went down a floor and tried to talk the Education Bureau into allowing some kind of lee-way for foreign monastics who take the bhikku/bhikkuni exam and failing to elicit anything more than a bored dismissal, I left Jogye Order. I wasn’t looking for the usual lower standards for us; I was wondering if we could do something like, possibly, take the test in English. Not this year, it’s too late; but maybe in the future? I was the only one with any enthusiasm for the idea. I walked out the doors and down the avenue, toward Gwanghwa-mun. I went to Kyobo Bookstore, hoping to find Milan Kundera’s Unbearable Lightness of Being. They didn’t have it. I picked up a new translation of selected Tranströmer and The Best European Short Stories 2011 instead, in a mild pique. No Kundera! And nothing about Havel! Only dictators and military states and recalcitrant bureaucracies!

I went out for Indian food, hoping dal tarka and roti and masala tea might be good comfort food. It was. Then I went back to Seoul Station and got on a south-bound train, to go home for the solstice.

Preparing small dumplings of glutinous rice-flour, to go into the solstice porridge.

The next day we made ong-shim-i, the small round glutinous dumplings that go into the traditional red mung-bean porridge. Red, to drive away demons and evil energies. I’ve never heard anyone talk about winter solstice as a kind of All Hallow’s Eve, but why else would we be concerned about warding away evil spirits, if not because at the winter solstice the veil between the spirit world and the human world grew more traversable? Why not, unless it was because we humans, who are in the Korean world always available to the influences of spirits, are even more vulnerable at the solstice, the fulcrum of the balance between light and dark?

The ong-shim-i are made to represent the returning sun, the Abbess of our seminary told us before we went on vacation. She didn’t then equate the dark purple-red porridge with the night, and I also resist making that symbolic equivalence even though the image works nicely. No; red is for protection and blessing in East Asia, and that’s why we make solstice porridge out of red mung-beans.

Mun Bosalnim rolling ong-shim-i.

It’s not as easy as you’d think to roll nice round dumplings. Skilled hands can place up to three pinches of dough in the palm and roll them quickly to spherical sameness, without mashing any of the little lumps together. I tried three dumplings at a time, and couldn’t manage the task, so I kept it to two dumplings.

The bosalnims, our women congregants, took over the making of the actual porridge, a laborous process taking up to several days. The mung beans must be soaked, then boiled, then strained, then re-boiled. The thick paste sinks to the bottom of the enormous cast-iron cauldron we use and tends to burn if the fire’s too hot underneath it or it’s not stirred regularly enough. The basic porridge can be neither too salty nor too bland. People add either sugar or salt to their individual bowls later, at the table.

On the actual day of the solstice, we filled two hundred square Tupperware containers with the porridge (re-heated and with the dumplings added in). These were offered at the main altar, all the side-altars, the ancestors’ altar. I couldn’t take any pictures because I was working—as per the reason for our vacation in the first place, to help out—and then helping conduct the ceremony. (I hit the moktak.) We then handed out the containers to all those who came to the midday service. The actual solstice was in the afternoon, about 2:20, and the Abbess of our temple instructed everyone to recite the Heart Sutra over the porridge before sharing it with family and friends at home. I made a quick run to my local immigration office and filled out stage-one visa extension paperwork, then made it back home in time to help with the quick afternoon solstice ceremony. (I hit the moktak again and read name-cards for the blessing.)

That evening, preparing to leave the next morning, I arranged my room, but less carefully than usual. It was December 22nd, and in another two weeks—a graduate—I would be back in this room anyway. Major organizing could wait.

I usually take the 6:05 am bus, which I can either ride all the way to Daegu or, as I planned to do this time, ride it only to Iksan and then get back on the railway. I thought I would go to Busan before heading back to school, to visit Gwangseong-sa, the Tibetan temple I attend. Maybe Geshe Sonam, the abbot, would be home; and even if not, I could do my practices and say hello to Geshe Lobsang.

Gunsan Intercity Bus Terminal, picture taken summer 2011

The older lady who runs the convenience store in the bus station was already open at 5:30 am. I bought motion-sickness medicine. Even the 40-minute ride on straight roads through the rice and barely fields of North Jeolla makes me queasy. Better safe than sorry. The store-owner has been watching me leave for school before the sun is up at the end of every vacation for four years. We exchange pleasantries. She’s Catholic, but I tell her to come to temple sometime. She smiles and laughs, yes, yes.

Iksan Station, with the Seoul-bound KTX pulling up to the platform.

I caught the train bound for Seoul, got off in Daejeon and switched back to the Gyeongsan Line and got on a train to Busan.

Gwangseong-sa, “Korea Tibet Center,” Busan.

Geshe Sonam wasn’t at Gwangseong-sa. He’s in India for the Kalachakra Initiation. Geshe Lobsang was home, though; as well as the gelong-la doing a 1000-day kido, reciting the entire Tibetan canon. “I’m reading Tsong-kha-pa now!” he told me, smiling. Originally from Ladakh, he’s read the entire canon twice before. I asked him how he learned English. “Oh, in Ladakh we have many tourists, European, Australian, some American. I learn from talking to them.” His hands are rough, chapped; he looks cold. I wouldn’t be surprised if the cold in the Dharma Hall was what caused the chapping. I remember how the monk who did the 100-day kido for Mu Sang Sa the winter I sat retreat there struggled to keep the skin on his knuckles from splitting in the sub-zero, bone-dry air of the Hall. Geshe Lobsang looked less miserable, dressed in only a single maroon sweatshirt over his lower robes. Gelong-la, on the other hand, had a hat askew on his head even during lunch and buried himself under a comforter while reciting in the Hall. I finished my prayers after lunch and then retraced my steps: street, subway, station, descent at Ulsan, taxi, bus station, bus over the pass, get off, walk up the road, enter the gates.

Afternoon, the path to Unmun-sa. Picture taken December 25th, 2011.

The period between the winter solstice and the lunar New Year’s, which is January 23, 2012, is typically referred to as “the little (new) year.” It’s one of those liminal periods, like a leap year, that emerges out of the overlap between two slightly different systems, in this case, the solar and the lunar. I like this “little year.” It lacks the pressure of a New Year or a Solstice, the once-a-year One Day that we typically take more seriously than we ought, relying too much on the concept of a significant singular moment. Resolutions, reviews, best-of’s, all congregate around this one day, New Year’s (and usually the solar new year, at that). But to spread out the significance over a month, to let it gestate, grow organically, to skip over the momentous moment and slip, slowly and smoothly, in the incrementally lessening dark, like swimming in the body of time, letting things go slow and easy, changing: it’s like entering a door. The whole body doesn’t enter, pass through, and exit a door all at once, and yet at the same time we can hardly pinpoint when, exactly, entrance became passage became exit. We just experience that we have, indeed, passed through.

(Happy solar New Year’s, which this time around is positioned nicely in the middle of the solstice-lunar new year period.)

*Correction: Havel did not receive the Nobel Prize; he was a nominee, not a recipient. Thank you to Tamarind Jordan Stowell for alerting me to the (regrettable; he ought to have received the prize) error. I’ve corrected the text.

lumbini, 2011

For the celebration of the birth of the Prince of Peace, an image from the birthplace of the Torchbearer of Mankind.*

Merry Christmas, y’all.

May all beings have happiness and its causes!

May all beings be free from suffering and its causes!

May all beings abide in equanimity, free from the extremes

of aversion and attachment!

May all attain awakening, the sweetest bliss!

*Ukkadharo manussanam, an epithet of the Buddha