Bhikkuni Ordination, April 3, 2012

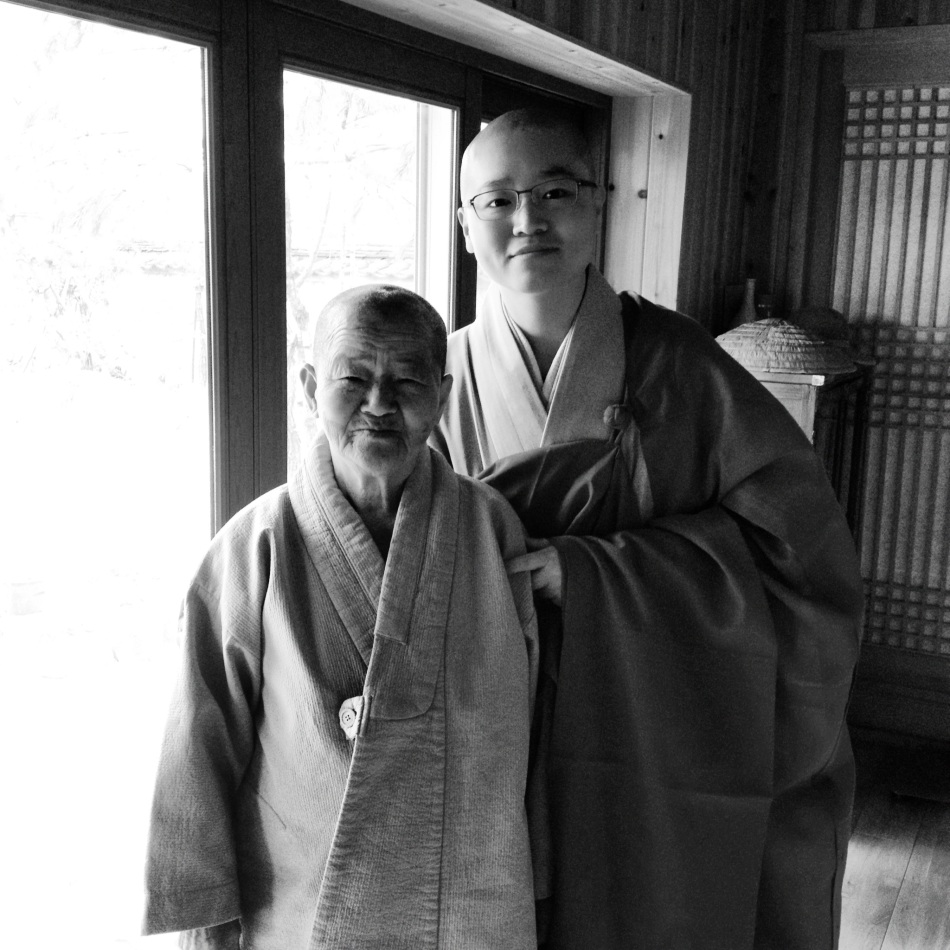

After bhikkuni ordination, with Hye Hae Noh Sunim.

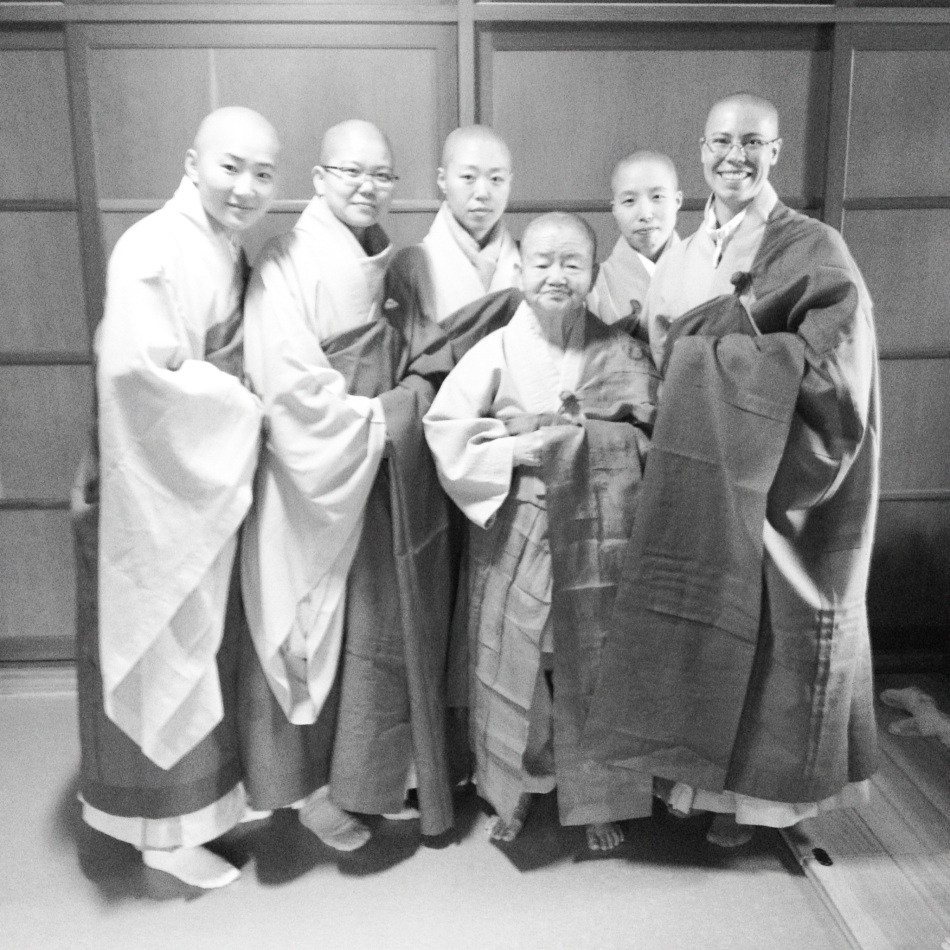

Left to right, Ji Mun Sunim, Hyeon Woo Sunim, Il Seok Sunim, Seon Myeong Sunim, Seon Joon Sunim

April 3, 2012, 3:40 a.m.

After a week-long training in the precepts, including lectures covering each section of the Pratimoksha precepts for bhikkuni, or fully-ordained female monastics, one hundred and eight women entered the Hall of Ten Thousand Virtues at Jikji Temple in South Korea and received the 348 precepts of a bhikkuni and re-affirmed her commitment to the eight “heavy precepts,” in accordance with the Dharmagupta (四分律) Vinaya lineage, from the community of elder nuns. Three acharya and seven “pure witnesses” formed the bhikkuni platform for transmission of the precepts.

When we were finished, we left the hall, ate breakfast in the formal style (a four-bowl meal, or “bal-ru gong-yang”), and then waited while the sami monks received their bhikku precepts. We then re-entered the Hall around 9 a.m. for our second ordination in front of the assembly of bhikkus. Our platform of ten senior nuns spoke on our behalf to the assembly of ten senior bhikkus, and the ordination ceremony was repeated in front of the monks. In this way, we received our ordination according to the “double platform” stipulated in the monastic regulations.

Ji Mun Sunim, Hyeon Woo Sunim, Il Seok Sunim, Seon Myeong Sunim, and Seo Ju Sunim with Hye Hae Noh Sunim

I almost don’t know what to say about our ordination. Almost; but I’m rarely someone at a loss for words for very long. I scoff at my own religiosity sometimes, mocking my love of pomp and ceremony while at the same time yearning for the glimpse of the sublime that I get from it, peeking out from under the skirts of priests and reflected, wavering, in the brass of candlesticks and offering bowls. I sniff at my own inclinations because they insinuate several things, one of which being that I am a sentimentalist, somehow cliche, and another of which being that I am unable to get past form and attain substance. It’s not that I am necessarily either of these, but the fear that I might be lurks around my love of midnight Christmas masses and my satisfaction in a well-timed rice-offering like a whisper overheard in a crowded room.

Ordination is a terribly religious business. If there is pomp, it will be on parade at an ordination. If there is form and attachment to form, it will be out menacing the community in full regalia. There are precepts and procedures and formulas and scripts. There are expectations to be met and traditions to be preserved. There is much at stake at an ordination ceremony, most of which can and will be committed to memory and later immortalized in the commentary of senior officials. If anything goes wrong, if anything goes extraordinarily well: either way, ceremonies are part of a religion’s public record and in this regard can raise the ire of those who think that function should take precedence over form. Does it really matter if the lines of the cushions are perfectly straight? Or the colors of the flower arrangements harmonious? Or whether we bowed in perfect unison or not?

I loved the training. The lectures, the group chanting of the Pratimoksha, the bowing, the repentance, the easy way a group of 108 women who received similar training at institutions across the country fell into the familiar rhythm of work and community life together. Camaraderie, and something more. A mutual respect for the difficulties we each overcame to arrive at this place, at this time, together. Shared karma and individual karma braided together like the rope of a ladder, leading us further on.

Jikji Temple, where I also received novice precepts six years ago, is beautiful. At that time, as a postulant I only looked at the ground (as befits a good postulant). I wore a track between the hall the female novices lived in for the three-week training and the bathroom and memorized the cracks in the concrete and the slope of the stairs, never once looking up to see the mountains or the the sky or the trees that grace the temple’s mandala. I was full of unresolved questions but an equally stubborn will to ordain, and the two shared space in my heart like a pair of bristling animals, granting each her territory but not allowing any trespass. I was in turmoil the entire postulant training, and I cried, overwhelmed, after our morning precepts ceremony on the last day. It would take me years to begin to shape a peace between my challenges to the system and institution I had entered into, and the practice—but not always the religion—to which I wanted to commit my life. Form and function, vessel and substance: endlessly, endlessly, I have struggled with the relationship between the two.

People ask me why I came to Korea, why I chose to ordain, why I chose to ordain in Korea. I am not singularly a Zen practitioner. I freely describe my practice as a hybrid between Korean and Tibetan practices. I also feel the Tibetan canon has much to offer that the Chinese canon (the one which is authoritative in Korea) cannot. I am more of a Madhyamakan than a Tathagatagharban; big trouble in East Asia. Given all that, Korea is not the logical choice for me. It was a choice among others, and I made it partly because I was told I could study the sutras and sit Zen if I wanted, but even more so, because I could receive precepts from the double platform. As a woman and an American, I cannot tell you all how important this was to me. From the day I met the Buddha-Dharma, I also met the sangha; and from the moment I met nuns (Tibetan-tradtion nuns, in Nepal), I wanted to be a part of their community, in the widest sense of “female monastics.” I also felt that ordination in America would be very difficult. I did not have a strong relationship with any one Tibetan teacher, and didn’t know how to forge one to seek ordination. I didn’t find any large communities of bhikkunis in the West at that time. I did not have a connection with Thich Nhat Hanh’s community, even though the Plum Village and Deer Park Monastery communities are among the most stable and structured large-scale monastic communities in the West. Other than going East, I just did not know what to do. Something just didn’t feel right for me in the States.

Being the nerd that I am, I researched monastic precepts after I left Nepal eleven years ago. I knew more about bhikkuni precepts, platforms, Vinaya lineages, and controversies than I did about basic Buddhist teachings for a couple of years. What I learned left me convinced that not only would I be satisfied with nothing less than full ordination, meaning the full precepts of a bhikkuni in addition to the ten “novice” or sramenerika precepts that constitutes the first-stage of ordination, but that it had to be done “legally.” That meant a community of nuns to transmit the training and the precepts, and another assembly of monks to affirm the ordination. This is the “double platform.” In practice, there are many nuns, including a large number in the Tibetan tradition, who don’t receive bhikkuni ordination. (In the case of Tibetan nuns, this is partly because the bhikkuni lineage died out. The ten precepts can be given to a woman by a bhikku, or male monastic, but strictly speaking, bhikkuni are required to ordain other bhikkuni; bhikku alone cannot transmit the bhikkuni precepts, nor can bhikkuni ordination by the nuns community alone without a second ordination by the bhikku community be considered a “legal” bhikkuni ordination.) Even in Korea, the double-platform wasn’t revived until the early 1980s, after a lapse of how many years I don’t know. Prior to that, bhikku only gave the bhikkuni precepts if a nun received them at all. Many monks and nuns held the ten novice precepts their whole lives, satisfied with that training and receiving all the respect and honor due to a monastic, with no one much bothering with the distinction between novice and fully-ordained. There is a lot more that could be said about monastic traditions and full ordination, but I’ll leave it at this.

When the Abbot of my Zen center in Connecticut told me Korea had a double-ordination platform for women and that I could receive not only monastic training, but scriptural training in Korea, I decided to come here and test my karma with this country. I had enough good karma to find a community and a teacher (Unsa Sunim) to take me. That was seven years ago. Although there were many, many other factors contributing to my decision to seek ordination in Korea, being able to receive bhikkuni precepts from the double-platform has always been the kernel and the core of that decision.

Whether I had “correct” or “clear” motives is not so important anymore; I am convinced that no one knows what they really want or feel until they’re in the thick of community and ordained life. Only when the pressure is on and the questions are sharp, sharper than they ever were before and sharper than you dreamed they could be, only then do you begin to understand why you’re willing to stick with the commitment you made. At least, that’s how ordained life as been for me. Not one decision, not one commitment, but a ceaseless recommitment and ever-deepening understanding of how and why I came here, and how and why I will continue to practice as a monastic.

I’m not sure how much I can talk about the details of the ordination ceremony. Sometimes ordination ceremonies are public, sometimes they aren’t; in Korea, outsiders are not permitted in, and certainly no non-monastics or monastics who are not of the correct monastic age (a novice nun who hadn’t received her intermediate precepts would not be allowed to even observe the ceremony, for example). But it was beautiful to me. The liturgy, a mixture of classical Chinese and formal high Korean, was intelligible to me for the first time ever; I understood only the Korean of my novice ordination and only bits of my intermediate/probationary ordination two years ago. The call-and-response, the swell of voices, the ritual of requesting everything three times; calling all Buddhas and Bodhisattvas to witness us and be our teachers and guides; the array of senior nuns on the platform, their severity, their grace; the sear of the precepts’ burn, the piney smell of the mugwort and incense as they smoldered; the hummingbird-beat of the moktak while we chanted the great dharani; the weight of the seven-patch robe of a dae kasa, the kasa of a fully ordained bhikkuni, the stiffness of the new material, the way I couldn’t untangle mine enough to give me space to properly fold my feet under it while we knelt, and so I kept tugging and tugging at while tucking my feet into a small ball so they wouldn’t peep out from under my robes; the nuns intoning in the dark and then the monks several hours later, “You will now receive your precepts-body;” the injunction to only use our Dharma names. Hearing that the Buddhas of the ten directions, the protectors, and all beings rejoice when someone receives precepts. Being told that our practice, as bhikkuni, is to “cease all wrong-doing, cultivate all good actions, and benefit all beings.” Hearing and feeling, truly and deeply and with incredible gratitude and joy, that as of this moment, I have a new life.

I guess that makes me a born-again monastic. There are worse things to be.

After the ceremony, a small group of us went to bow to the grand-teacher of one of our classmates. Seo Ju Sunim and I met seven and a half years ago as lay-women during the three-month winter retreat at Mu Sang Sa. We met again as a monastics at Unmun-sa, where were in the same class. Her grand-teacher, Hye Hae Sunim (honorifically called “elder,” or “Noh Sunim”), is one of the most respected nuns in the Zen community in Korea. Seo Ju Sunim suggested we go bow to her; I only had my phone to take pictures with, so the quality (I’m afraid) is less than what I would have hoped for as a photographer. Unless I told you, I’m not sure you’d know what to look for in the picture that indicates we’re full bhikkuni, other than (in my case) the way I can’t stop smiling. Our changsam, the gray butterfly robe we wear under our kasa, has no brown stripe at the collar; we also wear plain gray regular robes (jackets, etc.), without the brown stripe at the collar and on the sleeves. Our kasa is also paneled, or patched; the man-ui kasa we wore as novices and probationary nuns had no patches, but was a single contiguous piece of cloth. I regret somewhat to see, looking at the first picture in this post, that receiving new life as a bhikkuni has not helped me arrange my kasa any better. I am perpetually unable to get my folds to fall properly.

Hye Hae Noh Sunim, whose name means “Ocean of Wisdom,” gave us a few words on hwadu practice. Then she exclaimed over the cake we’d brought her, laughed, congratulated us, and urged us to eat slices of orange. She was barefoot on a blustery spring day. She has few teeth left but very sharp hearing. She is one of the strengths of the bhikkuni community here in Korea. It is because of practitioners like her, elders who found their way to the marrow of the bone of their vocation and their practice and then built communities to help other women practice, that we were able to receive precepts at all yesterday morning. In the past lies the future, like the braids of a rope ladder, anchoring us in the moment while taking us onward at the same time.

I’ve always been aware that even though we say, “I took precepts,” this is not precise or accurate language. We don’t take precepts, they cannot be lifted like a stereo or claimed like a prize. We receive them; they are given. We don’t keep precepts, either, like a casserole in the freezer or cash in an account. We hold them, like a living thing, and we care for them, and they care for us. We may break precepts, like a heart, or a bone; but they don’t break like something inanimate. They break like we break, because they live as we live, and they die as we fail to respect and love them, to see them as that which will shape us into beings capable of helping other beings and guide us toward wisdom and skillfulness, for the greatest benefit and joy of all.

I am so grateful to everyone who has supported my sisters and me on the path. Near and far, across continents and oceans, many different lives have interwoven with mine to make this vocation possible. May I repay this debt in full, and fulfill my vows, world after world, life after life, until every being is free.

Beautiful, Seon Joon.

April 4, 2012 at 11:42 pm

Oh, Seon Joon, this is such a beautiful post. Thank you, thank you, so much, for opening even this window into your experience and your ceremony. I loved reading about your ordination (it makes me want to go back and read my own post about the day of my rabbinic ordination — I may treat myself to that trip down memory lane when I take my lunch break today!) and I love also your meditations on the tensions and struggles and the things which have changed. I’ve never experienced rituals like the ones you describe here, but in your words and images I often feel that I’m catching a glimpse of your religious life, and it is beautiful to me.

I resonate deeply with what you say about how precepts are given, they are received, not “taken” per se. The same is true, I think, of rabbinic smicha (ordination); and, in a broader sense, of what we cal kabbalat ohl shamayim, “receiving the yoke of heaven,” the traditional term for accepting the commandments. In order to receive, one needs to be open; but openness itself isn’t enough, or isn’t the whole picture. There is a subtle change. Something flows through us.

When I was ordained, I remember feeling — in that moment, with the hands of my teachers pressing on my shoulders as they recited the words which changed me from a student into a rabbi — a little bit like how I felt when I gave birth to my son. Something was moving through me, something was pouring into me from beyond, something which would change me in ways I couldn’t begin to understand…

I wish you every blessing upon this auspicious occasion! I send much love.

April 5, 2012 at 12:44 am

Dearest Rachel, thank you…

April 6, 2012 at 7:38 pm

A wonderful story, and a well and finely written post. I’m pleased for you, and the satisfaction and reward you feel.

April 5, 2012 at 1:28 am

Now it begins!

Big hug.

April 5, 2012 at 2:13 am

And so it does!

April 6, 2012 at 7:38 pm

This is beautiful. I wish you would submit it to one of the Buddhist magazines like Buddhadharma or Tricycle so a wider audience can get a taste of your sincerity.

With the deepest gratitude for your effort,

P’arang Geri Larkin

April 5, 2012 at 2:32 am

I’m honored you read this! I’ve not thought about submitting anything to magazines, but I would be grateful if nuns received more attention in the Western Buddhist press. But, thank you, and with deep bows to an older sister in the Dharma…

April 6, 2012 at 7:48 pm

“All buddhas of the ten directions, all bodhisattvas, and all beings rejoice”! Me, too — there with you, as you were once with me in the zendo at Bultasa when it was only the two of us week after week, and as you were with me at the prison in Michigan City. Dae Soen-sa Nim would say, “Our dharma bodies have never been separate,” but never more together than when buddhas and bodhisattvas and all beings everywhere filled that ordination hall! I’m so proud of you!

Much love,

Ron (Ja Gak, may it one day be!)

April 5, 2012 at 11:20 am

Oh Ron, thank you! I hope that I’ll be able to sit with you again at Bultasa sometime in the near (and far, but preferably near *and* far!) future. With deepest gratitude to a brother… palms together.

April 6, 2012 at 7:49 pm

‘The buddhas of trhe ten directions, the protectors, and all being rejoice!” Me, too — there with you as you were with me in the zendo at Bultasa. week after week, just the two of us, and as you were with me as we went to have zen practice in the prison in Michigan City. Dae Soen-Sa Nim would have said, “Our dharma bodies have never been separate, lifetime to lifetime,” but never more so than when all the buddhas, bodhisattvas, protectors, and all beings everywhere filled that ordination hall!

I’m so proud of you!

Love,

Ron (Ja Gak — and may that one day come to pass!)

April 5, 2012 at 11:24 am

Camaraderie, and something more. A mutual respect for the difficulties we each overcame to arrive at this place, at this time, together.

First, congratulations on your ordination – gassho! (Sorry, I don’t know the Korean term 🙂 Also, thank you for sharing this lovely and moving reflection, and thank you particularly for this quote – it captures perfectly something I have always felt in my Aikido dojo community (where we also do an intense physical and spiritual practice!), but have never quite been able to put into words. Now I have them.

April 5, 2012 at 8:01 pm

Erik, thank you for your congratulations, and I’m so glad that you found a way to express your experience. “Together action” (I don’t know the Japanese term!) is one of the most important aspects of practice in Korea, and so I know what it must be like to share–and grow–together in the dojang. We say “hapjang” in Korean, which is Sino-Korean for “hand/palms together.” Hapjang!

April 6, 2012 at 7:51 pm

Congratulations, Sunim, on completing your training and receiving full ordination. And thank you for this heart-felt expression of the path you’ve taken and its meaning to you in this year of the dragon.

Barry

April 5, 2012 at 11:09 pm

Thank you, Barry. Palms together!

April 6, 2012 at 7:03 pm

Dear Seon Joon, I am thrilled for you, and cried tears of happiness on seeing these beautiful photographs. I will pray for you tonight at the Easter vigil: to me, the deep message is the same: May we love one another, may our hearts be as one, may we all cease wrong-doing, may all beings one day be free. Sending you love from chilly Montreal, where the magnolias are beginning to bloom but cherries are only a dream!

April 7, 2012 at 7:53 pm

Dear Beth,

I’m late getting home after a week on the road, but thank you so, so much. Your words many years ago–that monastics and prayers are the hidden engines of the world–have resonated with me, giving me strength and aspiration again and again, all these years. Thank you.

April 14, 2012 at 4:54 pm

Congratulations on receiving the bhikkuni precepts Sunim! I am so happy for you, so proud of you, so grateful and honoured to have met you along this path and travelled beside you for a spell. What you wrote about “holding” rather than taking the precepts is particularly striking and gives this layperson some comfort and much needed perspective regarding her own vows and commitments. I wish you all the best and not only hope but know that our paths will cross again. Until then, I hope to continue reading your observations, insights and inspirations. Great big grinning hapjang!

April 9, 2012 at 9:24 am

Dear Seon Joon Sunim–Congratulations on your ordination, and thank you for your hard work and perseverance, Thanks also for sharing your experience–you make it real for us.

With many bows

Douglas Floyd

April 13, 2012 at 3:50 am

Seon Joon Sunim, I’ve been following your blog after finding it about a year ago, after my overnight visit to Unmunsa, which remains one of the most meaningful experiences of my adult life. (That sounds terribly dramatic, but it’s all relative.) I don’t know what happened there—just some small things that were big enough—but in the midst of this rather confused and floating life of mine it remains a rare experience of clarity. Thank you for this post, which I have read twice or three times now. Somehow reading about your ordination and your spiritual history has, for me, gathered up the edges of the fabric woven by accounts of other Westerners’ monastic experiences in Korea (Buswell, M. Batchelor). It’s a really deep and beautiful piece. I congratulate you on your ordination and wish you well in your life as a bhikkuni.

April 15, 2012 at 8:32 am

Pingback: cold mountain (34) (35) (36) « 如 (thus) 是

Congratulations!

April 19, 2012 at 10:34 am

Hello Seon Joon Sunim,

Congratulations on receiving your precepts. I’m so happy to see that you have the blog running once more. Are you still at Unmunsa?

Again, congratulations on all your hard work and perseverance.

May 24, 2012 at 9:00 pm

a nice post … very personally . I like the photo … Walking the road to Heungryun-sa …. it is beautiiful!

July 21, 2012 at 4:49 pm

Dear Venerable,

You mentioned not knowing about large Western Bhikshuni communities in the past, but perhaps you are now aware of Sravasti Abbey in Washington or Chenrezig Institute in Australia? Sravasti Abbey now has enough Bhikshuni residents to be a formal sangha. While lacking the resources that large Korean communities have, perhaps they may be of interest in the future.

August 22, 2012 at 5:27 pm

Res Ven

i am from india . we are doing work for reviel of buddhism in india , there is many shakya family in north india we are working among them . may you know we have no more monks in india so we would like to invite you for thanmma talk . please visit http://www.ybsindia.org

thank you

August 23, 2013 at 1:19 am